Standing in an art gallery can be intimidating. Even for an art lover. How long to devote to each piece? On one hand, not looking at a work long enough might indicated a lack of proper attention. On the other hand moving too slowly is just boring. Are you underdressed or overdressed? "It’s a universal experience." says artist Jonathan Leach, "people feel uncomfortable in galleries."

And if Leach is willing to admit to being uncomfortable in gallery spaces, those of us who aren’t calmly self-assured Art Institute of Chicago-educated painters don’t stand much of a chance.

He adds, "Everyone says that their work is open to interpretation. But then they deny people access to their work intellectually, but also physically as well. The gallery system [can be] standoffish, it [can] distance you from the art by putting you in a very unnatural setting."

No one blames the galleries for this distance. They are, after all, businesses, and making a profit off of selling art is a daunting proposition in the best of times.

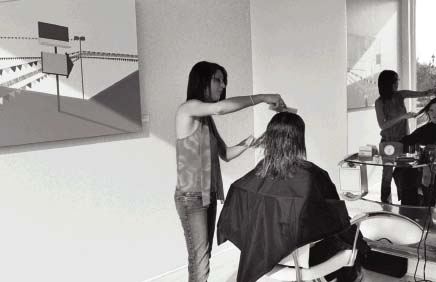

Although Gallery Hop has done much to dispel the intimidation factor about galleries and museums for the average Joe, it’s because of this generalized anxiety that Leach is so eager to talk about a recent trend in the art world over the past few years—using hair salons for gallery spaces (his own featured in the Color Room).

"It’s great," he says. "People go in there to relax, they sit down and then they have nothing to do for the next few hours but look at what’s on the walls.

"It’s great," he says. "People go in there to relax, they sit down and then they have nothing to do for the next few hours but look at what’s on the walls.

Ann Tower (of Ann Tower Gallery) says of salons that double as gallery space, "I think it iswonderful. The more art that's out there the better. Lexington needs that. You might find a higher lever of art expertise in a gallery—after all, that it their job— but showing in a salon space is still a wonderful opportunity for artists."

Time is often the greatest educator on any particular piece of art. A stock assignment for upper level art history students, is to spend up to 18 hours looking at the same piece. This is a little excessive for most, but it can’t be denied that close observation leads to greater apprehension, and with that increased familiarity increased affinity.

Or possibly hatred, people can just as easily dislike something as they can like it after all. The important thing is that people invest enough in a piece to have a response to it.

"That reaction is critical." Said Leach. "Otherwise people just eat the snacks [at an opening], leave and say, ‘well that was odd.’ No one talks about art in a gallery, they only talk after they’ve left it. They’re too afraid of sounding stupid when they’re in that environment—me too. But it’s vital that people not be intimidated by art."

This could sound like the naiveté and pretension associated with the worst sort of shaggy haired, attention challenged nabob, the kind who always talk about how art is "for the people" and then explain why you don’t "get it"—presumably because everyone else is less assured of their genius than they are themselves.

But Leach is thoughtful, and good at what he does. In addition, his work draws from sources that are immediately relevant to everyone, landscapes that capture in color and geometry the places where we live and work; suburbs, strip malls, dazzling skylines of downtowns. The relationship with commercialism, both materially and psychologically is one of the touchstones of Leach’s work. It’s a theme evoked explicitly in his subject matter? the bright, oddly familiar urban landscapes visible from any American highway? and subtly in his spare, sterile treatments of streets and buildings.

It is art without sentimentality, not least because it is representative of areas that are often denigrated, but rarely sentimentalized. When was the last time you heard a paean to urban sprawl?

"In terms of my art I don’t look at it as a moral question," says Leach. "I’m not saying that these places are good or bad. I’ve survived them. They are a byproduct of our lifestyle."

But there is also a deep sense of irony that runs through these paintings.

Historically, landscapes have been used to venerate and idealize nature, but Leach’s subjects are the antithesis of that, used car lots, cluster housing developments, and drive-ins. He paints the true American language of buying and selling.

Jonathan Leach walks the one of the finest lines of contemporary art, creating work that is intellectually evocative and visually interesting. He rejects what he calls "the trend towards compulsive analysis" that has hijacked postmodern art. "In a dangerous sense," he says, "Postmodernism allows for the domination of ambiguity and disconnection, as if contemporary art has given up on the viewer."

"It seems like so many artists are, well, not lazy. But they seem to add un-needed ambient noise to their work." In other words, they tell you that a piece can mean anything you want it to. Then turn around and say you can never understand it because everything is too personal for us to really understand each other.

Situated in Turfland mall, on the highly commercialized Harrodsburg road, The Color Room could easily be a feature in one of Leach’s paintings. The well lit, open space, with its brightly colored accents seems like an ideal place to display art. Leach’s paintings, which are hanging in The Color Room until November do especially well here, their bright colors complimenting the spacious and modern feel of the salon.

In fact, Leach was originally chosen to show here because his work was such a good fit with the Salon’s contemporary feel. His show, which has hung for two months already is the inaugural exhibit at The Color Room, but owner Larry Holleran is eager to continue the use of the space as a gallery.

"It’s a great situation for everyone." He said. "The artist gains visibility and hopefully sells some work, and we get to add visual interest to our space."

Another salon/gallery owner in Lexington, Sonya Forshcner, owner of Ivos, agrees. Forshcner might not have invented the idea of melding a salon with a gallery, but she has certainly honed it in Lexington.

Another salon/gallery owner in Lexington, Sonya Forshcner, owner of Ivos, agrees. Forshcner might not have invented the idea of melding a salon with a gallery, but she has certainly honed it in Lexington.

When she moved from her campus location to her new salon on Mill Street last year Forshcner planned the renovation of her space with a gallery in mind, from the spare ness of the decoration to the picture rails and commercial gallery-standard lighting.

Forshcner has been tremendously successful with her art shows. For the past three years she has booked artists at least twelve months in advance, and of the past four shows, three have sold 85 percent of their work. Each artist shows at Ivos for one month. Since it is not a commercial gallery, the artist is in charge of any opening reception, as well as for hanging the pieces. Unlike most galleries, commercial or otherwise, Forshcner doesn’t charge any commission, instead she receives a piece of art at the show’s close.

One of the biggest advantages salons have when displaying art is that they need not generally be concerned with profit. Since Forshcner doesn’t take a cut (commercial galleries often assess 40 to 60 percent) the artists are able to price their work lower, and sell more pieces, to a more financially diverse audience.

"At first I charged a small commission," she laughed, "but then ended up buying a piece every time anyway. I don’t want to make money off of the gallery, I do it for the artists. On the other hand I didn’t want it to cost me that much either. This way everyone wins."

Since the primary income comes from the salon, the gallery doesn’t need to be profit driven. This gives Forshcner a lot of flexibility when selecting artists

The artists featured at Ivos draw from all ages and mediums, but Forshcner often prefers to work with the younger, lesser established artists. "I like the fresh look." She says, "often their work is rawer and more edgy. In addition its great to see them improve over the years. Some of the artists she shows have been at Ivos many times, so she gets to see their progress and improvement.

"Salon and gallery mean the same thing." Said Forshcner. "The way I see it there is no difference. I’m an artist at what I do, and through that I have an opportunity to help other artists in the community. I try to set this up to make it as easy as possible for them."

The current artist showing at Ivos, Derek Ball agrees that Ivos is a great place to show work.

"Everything in there leads the viewer to the art." He says, "The lighting, the simplicity of the space, if you took the chairs out, you wouldn’t know that Ivos wasn’t primarily a gallery."

Ball is no stranger to showing his work in non-traditional spaces. His last photography show hung in Vigny’s café on Limestone.

"There’s something very appealing about putting my work in spaces that are activated for other reasons." He says. "People aren’t at these places to stare at the walls. Knowing what goes on around the work, the bustle and the gossip, and that my work will become a part of that experience is gratifying."

But he is equally open to discussing the negatives at showing art in a non-designated arts’ space. "Obviously you won’t get the dedication to a piece that you would get in a gallery. Like I said, people aren’t there to stare at the walls. Showing outside of a formal gallery also means less exposure to the art community. A lot of the people who will see your art in these non-gallery spaces wouldn’t otherwise be exposed to it, or anything like it probably." He paused. "That can be good and bad. On one hand it’s very exciting to introduce your work to new people. On the other hand most of these people won’t commit to the work the way people might in a traditional gallery."

But he is equally open to discussing the negatives at showing art in a non-designated arts’ space. "Obviously you won’t get the dedication to a piece that you would get in a gallery. Like I said, people aren’t there to stare at the walls. Showing outside of a formal gallery also means less exposure to the art community. A lot of the people who will see your art in these non-gallery spaces wouldn’t otherwise be exposed to it, or anything like it probably." He paused. "That can be good and bad. On one hand it’s very exciting to introduce your work to new people. On the other hand most of these people won’t commit to the work the way people might in a traditional gallery."

"I see an attitude from young artists," he says, "people who haven’t worked a lot yet. It’s easy to be down on the commercial gallery system, saying that it’s corrupt and sterile and classiest, and whatever. But you have to decide whether you are going to play that game or whether you are going to go work in a truck somewhere."

Ball knows a lot about the investment of time that goes into art. His show in Ivos this month is the first step in a collaboration with fellow artist Kristina LaFollette that began ten years ago.

The these photographs on display are culled from an original body of three hundred images. The photographs are evocative, mysterious images which simultaneous defy and demand explanation, but Ball shies away from talking too specifically about his work.

"They’re psychological portraits, and stories. But for me to describe them too closely takes something away from the pieces I think. Each photograph tells a story, but that story is up to the viewer."

So does Ball play the game? "Well, sometimes." He admits. "Not recently. But if a gallery offered to represent me I certainly wouldn’t turn it down. Salons can never replace galleries in flexibility or attention to the art."

Which is certainly true. Rather salons are offering communities a new venue in which to appreciate art, especially that of younger, less exposed artists.n