A Man For All Seasons

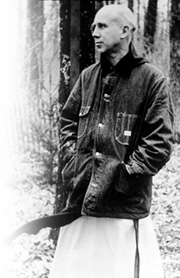

People still connect with monk from Nelson County.

By Chris Webb

People who don't even believe in God still believe in Thomas Merton.

People who don't even believe in God still believe in Thomas Merton.

More than 30 years after his untimely death, fascination with the Trappist monk as a spiritual force in our own time only escalates.

Why do they continue to turn to this "farmer from Nelson County?" What is the enduring attraction? Unquestionably, Merton was one of the most influential monks in history. He has a wide readership, one that is not primarily monastic. Some would even argue that his writing is as popular among the secular as it is the spiritual and/or religious audience. His autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, is a modern classic, still in print after more than 50 years, translated into more than 20 languages, and on several lists as one of the top 100 books of the last century.

As the anniversary of his death approaches (on December 10), it becomes increasingly clear that he's made an enduring, visceral connection - as artist, writer, thinker, teacher, social advocate - that transcends even his extensive literary and philosophical contributions.

One of my favorite stories about Merton," recalls Maurice Manning, winner of the 2000 Yale Series of Younger Poets, "is one that Will Campbell, the Baptist preacher and civil activist, shared with me.... One of the people who was attracted to Merton in his time was the author Walker Percy. Merton had written a couple of articles that Campbell published in Katallagete, so they were acquaintances. Percy, also a friend of Campbell, asked to be introduced to Thomas Merton. So they made arrangements to see him and drove up from Tennessee to visit the monastery. Now, by this time, Percy was famous in his own right, having won the National Book Award. But Percy was ready to humble himself in front of this great religious man. He was expecting some great revelatory encounter.

"When they got to the monastery, Merton was itching to go for a ride in the car. So they went and bought a six-pack of beer, came back to the monastery, and sat around talking and drinking beer. There's something about that story that... impressed me. Here's a guy that was so revered, looked upon as such a holy figure, a man so absorbed in his spiritual life, that socializing in this way seemed like a completely foreign concept. But the truth was, behind his persona and all the important things he had to say was this guy who was really down to earth, apparently interested in connecting with people in a very simple and honest way."

"Thomas Merton," says Ray Smith, a local musician and songwriter, "basically rescued Christianity from the Pat Robertsons of the world as far as I was concerned. For me, he reconceptualized and remystified Christianity. East-West dialogue. Meeting with the Dalai Lama. Incorporating Zen. Having a drink with Walker Percy and Will Campbell. This was a refreshing model of the Christian identity."

"Merton was writing," says Gary Houchens, a teacher at Christ the King School, "in a way that challenged contemporary culture in several ways. First, with social justice teaching, where Merton raised issues that comfortable Christianity tended to overlook. But also, by playing witness to a very universal humanistic element in Christianity."

In many ways, Merton energized monastic theology and gave it an extraordinary relevance for the contemporary world.

"Also," adds Houchens, "Merton was a very paradoxical person. He understood his own identity to be wrapped up in paradox. He was a poet, an artist, and an activist who chose to live the life of a monk. And in his ancient yearning for wisdom, he brought together many different, often opposing forces, like politics and religion, and was able to identify with them all."

Naomi Burton Stone, Merton's literary agent and close friend has written, "Each one of us knows a different Thomas Merton." because Merton's interests are so varied and because he wrote with such a universal humanity, he is able to reach just about anyone.

The Examined Life

To Merton, faith and dialogue were more about asking questions and exploring oneself than delivering the answers. With sensitivity, he attempted to live an examined life amid all the contradictions of the world. Merton's approach was genuinely human, as a man struggling like the rest of world to find meaning. Though he lived in a monastery, his life was still one filled with decisions to be made and questions to be answered. And his writing challenged people to see beyond the surface, beyond the transitory, to get to the enduring human values.

Jonathan Montaldo, director of the Merton Center at Bellarmine University in Louisville and co-editor of The Intimate Merton, points out that, "Merton's gift is to write in such a way that you forget about him talking and think of yourself and identify. He seduces you to identify with him. He speaks directly to you. When you read Merton, it's like a mirror... you see a bit of yourself staring back."

Merton's readers find a spiritual writer who isn't shy about his own experiences and personal struggles. Rooted in religious tradition, he was continuously searching for and embracing the truth no matter where he found it. He was honest about his conflicts and shortcomings, reaching deep down and touching the injuries of each person's mind and spirit.

Merton's own personal history also reveals a man of struggle and conflict, of temptation and suffering.

Brother Paul Quenon, a monk, poet, and photographer at the Abbey of Gethsemani who studied as a novice under Thomas Merton, says "Merton was somewhat of a drifter in his youth. He attended the best schools. Yet, he converted to Catholicism and plunged into the deepest mysticism that was available to him. And he did so with a breadth of mind and spirit, a wit and insight, that gives his story and his writing so much appeal. Nowadays, there are lots of young people who don't know Thomas Merton at all. But many end up finding him somehow, and when they do, they connect with him and love him."

Dr. Don Nugent, a retired history professor from the University of Kentucky who has written and lectured extensively on Thomas Merton, believes that "Merton's universality is a definite magnet. He speaks in such a way that people all over the world feel as if he's speaking directly to them. He reaches a wellspring of humanity where he can speak for humanity at large."

"Merton was a great teacher," adds Montaldo. "He speaks in such a way that you can't help but get interested in what he gets interested in. You look at the world with him, then you open the window and climb through with his enthusiasm and go beyond the teacher to experience it yourself."

'An American Lama'

As a student of the world, Merton's interests were many. Reading widely on the literature of the day, he remained in touch with broader elements of culture. Staying informed on political and social issues of the world, he spoke out regarding war, racism, and inequality.

"Merton's interests were very wide," says Montaldo, "and so his audience is very wide. Merton wrote and spoke out about social justice, which tends to have a much wider appeal than monastic spirituality."

Thomas Merton was a person of cosmopolitan tastes. A fan of many types of music, including jazz and classical, Merton was open to just about anything. He was intrigued by Bob Dylan's music, especially as social criticism. He wrote about and studied the likes of William Blake, James Joyce, Boris Pasternak, William Faulkner, Rainer Maria Rilke, Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Albert Camus, T. S. Eliot, John Milton, and many more.

Later on, especially in the last decade of his life, Merton's interest in other religions began to take on more prominence.

"Besides engaging in contemplative practices," says Montaldo, "Merton had extensive dialogue with practitioners of other religions all around the world."

Not one to be fenced in by Catholic tradition, Merton studied Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Sufism, Buddhism, and so on. In his research, Merton discovered striking similarities with the teachings of Christianity and became a crusader for a return to life that is balanced between action and contemplation and an advocate of cooperation and brotherhood between East and West. Eventually, Merton's openness to other religions, especially Asian religions, helped him to focus his vision and deepen his understanding of life's mystery. Merton, in his many dialogues, even conversed with the Dalai Lama, who went so far as to call Merton, an "American Lama."

Though he very much valued solitude, Merton corresponded with over a thousand people, including Ernesto Cardenal, Dorothy Day, Ethel Kennedy, Aldous Huxley, Pope John XXIII, Pope Paul VI, Zen master D.T. Suzuki, and Muslim friend and Sufi master Abdul Aziz, among many others. Making every effort to identify with people, he always attempted to find "the hidden ground of love" on which to comfortably meet.

Angeline Robertson, a local artist and student at the University of Kentucky, points out that, "Merton touches you in a way that you feel totally comfortable. He just has this peculiar way of talking directly to you and changing you. He's a writer like no other I've come across. I've often heard people refer to him as kind of a rebel. And I guess he was. He challenged many accepted conventions, asking questions about established ways of doing things. He was rebellious in that he defied the status quo and pushed for reform in all aspects that would nourish the spiritual life. He went against the grain a bit, pushing for his essays on social concerns to be published, despite the advice and urging of his peers. He remained open to the world and to other people in so many ways, yet he followed a path that was singularly his. Many people my age, college students, have really taken to Thomas Merton..."

The Legacy

Lawrence S. Cunningham, author of Thomas Merton: Spiritual Master, wrote that, "Merton, in short, was capable of entering the larger world of cultural discourse while rooted in a tradition that gave a peculiar weight and a ring of authenticity to his words."

Dr. Nugent adds, "I truly believe that Merton was one of the great spiritual thinkers of the 20th century. He has the ability to reach virtually everyone at some point, as poet, as social critic, as storyteller, as historian. He was interested in virtually everything and everyone. He had dialogue with Joan Baez and corresponded with teens, many of whom sent him music to listen to. He had a wonderful sense of humor and a genuine mystique."

"And Merton wasn't just an academic," adds Nugent. "He lived and dealt with the things he wrote about. Anthony Padovano, in his book titled The Human Journey, called Merton a 'Symbol of a Century'. I truly believe he's gonna be a man of the 21st century as well."

Another testament to the magnitude of Merton's appeal is the continuing development of the Merton Center at Bellarmine University in Louisville which was founded with Merton's cooperation in 1963. As the major repository for Merton's work, the Merton Center houses over 800 of his drawings, over 600 audio tapes of his lectures and teachings, and over 1200 of his photographs. The Merton Center contains more than 40,000 Merton-related items in all, and gets a bit bigger every year.

Merton still emerges in contemporary journal articles that continue to explore his writings. There are even two journals specifically devoted to Merton, The Merton Seasonal and The Merton Annual. All around, people gather together in groups, as Merton Societies, for conferences, and lectures. In fact, there are twenty-five chapters of the International Thomas Merton Society all over the world who meet on a regular basis.

In short time, many of these societies will gather to honor Merton as the anniversary of his tragic death approaches. On December 10, 1968, Thomas Merton passed away, exactly twenty-seven years from the day he first arrived at the Abbey of Gethsemani.

Neither Merton nor anyone at Gethsemani could have predicted the impression he would make on the world for years to come.

Thomas Merton has assisted in the spiritual journey of thousands of people, many of them decades after his untimely passing. But more astonishing is the fact that some of these people, forever changed, have as their only link with any form of spirituality whatsoever, a Trappist monk who lived in Nelson Country, Kentucky.

The online version of this story will also include a selected bibliography of works by and about Thomas Merton.

"The basic sin, for Christianity, is rejecting others in order to choose oneself, deciding against others and deciding for oneself."

-from Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander

"I got a lovely mad letter from a sixteen-year-old girl in [Campbell] California [Susan Butorovitch], saying she and a friend were running an 'underground paper' and wanted me to send them something. They sounded very Beatle-struck, and suggested as subjects for me, besides 'fight the baddy baddies,' that I might also 'promote Lennonism.' So I sent them a piece of a new poetry-prose mosaic that I think New Directions is doing next spring. I don't know if it promotes Lennonism, but perhaps it is tinged with Dylanism."

-from a letter sent to June J. Yungblut on June 22, 1967, taken from The Hidden Ground of Love

"Our real journey in life is interior: it is a matter of growth, deepening, and an ever greater surrender to the creative action of love and grace in our hearts."

-from The Road to Joy

"Perfect spiritual freedom is a total inability to make any evil choice."

-from New Seeds of Contemplation

"As a priest and monk of the Catholic Church I would like to add my voice to the voices of all those who have pleaded for a peaceful settlement in Vietnam. A neutralized and united Vietnam protected by secure guarantee would certainly do more for the interests of freedom and of the people of Southeast Asia, as well as for our own interests, than a useless and stupid war."

-from a letter to Lyndon B. Johnson, dated May 31, 1964, taken from The Hidden Ground of Love

"Every step I took opened up a new world of joys, spiritual joys, and joys of the mind and imagination and senses in the natural order, but on the plane of innocence, and under the direction of grace."

-from The Seven Storey Mountain

"There is no greater disaster in the spiritual life than to be immersed in unreality, for life is maintained and nourished in us by our vital relation with realities outside and above us."

-from Thoughts in Solitude

A Monk's Life

Thomas Merton was born in Prades, France, on the last day of January in 1915, to artistic parents, Owen and Ruth Jenkins Merton. The following year, World War I forced the Merton family out of France, and they took refuge in America. In 1921, by the time Thomas Merton was six years old, his mother passed away from cancer. Several years later, father and son moved back to the south of France, this time settling in St. Antonin and in the following years, the young Thomas would begin studies at Lycée Ingres in Montauban, France.

In May of 1928, Thomas again moved, this time to Ealing, West London, England, to live with his Aunt Maud and continue his studies at Ripley Court in Surrey. It was around this time that Thomas first admitted his desire to be a writer. In the summer of 1929, while on holiday in Scotland, Owen Merton fell ill and was hospitalized with a malignant brain tumor. Owen passed away in January of 1931, and Thomas, then 15, was forced to ponder the mysteries of suffering, and religion did little to comfort him.

Thomas himself came close to death around the age of seventeen when a toothache revealed an awful infection, his entire body pumping poisoned blood. Thomas survived, returned to his novels, and did so well in school that he won a scholarship to Clare College in Cambridge. At Cambridge, Merton fell prey to a period of bewilderment and promiscuous behavior. Unpleased with his conduct, Thomas' guardian sent the confused Merton back to America where he would eventually remain. In 1935, Merton began classes at Columbia University in New York.

At Columbia, Merton would be editor of the Columbia Yearbook and art editor of the Jester, a campus magazine. Merton's need for spiritual development began to grow. In 1938, Merton received his Bachelor of Arts degree and was baptized as a Roman Catholic. He obtained his Master of Arts degree in 1939 and began writing book reviews for New York newspapers. After briefly teaching at the Columbia University Extension, Merton began teaching English at Saint Bonaventure's College.

In 1940, Thomas found out that he'd been rejected as an applicant to the Franciscan order. The next year, Merton went on a retreat at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Trappist, Kentucky, and on December 10, 1941, Merton officially entered the Abbey of Gethsemani to be a monk and priest.

Merton wrote extensively in the years to follow on social concerns, contemplative prayer, and his own religious experience. In 1948, Merton's autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, was published to critical acclaim. As novice master, Merton helped educate new monks and deepen their faith. He also wrote poetry, made drawings, and took photos.

In the last decade of his life, Merton became increasingly interested in other religious traditions and fascinated by the spiritual treasures found in the faith of Jews, Sufis, Hindus, and Buddhists. In 1961, the monastic community at the Abbey of Gethsemani built a hermitage for Merton about a mile from the monastery and in 1965, he was given permission to live there full-time. Merton lived in this hermitage, reading, writing, and praying, until his death. In late 1968, Merton left the country to visit Asia. In Bangkok, Thailand, on December 10, 1968, on the twenty-seventh anniversary of his entrance into the monastic life, Merton passed away, victim of an accidental electrocution. His body was brought back to the Abbey of Gethsemani, and he is buried in their small cemetery next to the abbey church.

Upcoming Events

"Kentucky Writers Read Thomas Merton," will be co-sponsored by the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University and the Kentucky Writers' Coalition. Kentucky Poet Laureate Richard Taylor will lead several of the state's top writers, including Dianne Aprile, Marcia Hurlow, Thomas Oates, Ron Seitz, Frederick Smock, and Mary Ann Carrico-Mitchell, as they gather to celebrate writing in Kentucky. Writers will read selections from Thomas Merton's catalog as well as excerpts from their own works. The event also includes a reception with refreshments, live music, and the release and booksigning for Louisville author Dianne Aprile's new book, Making a Heart For God: A Week Inside a Catholic Monastery, featuring a foreword by Brother Patrick Hart and photographs by Josh Shapero and Brother Paul Quenon. "Kentucky Writers Read Thomas Merton" is scheduled for December 2 at 7 PM at Bellarmine University's Craille Theater. Admission is $5 at the door, with proceeds to benefit the Thomas Merton Center and the Kentucky Writers Coalition.

The second event will feature Harold Talbott, a convert to Roman Catholicism who was baptized as an adult. Receiving the sacrament of confirmation at the Abbey of Gethsemani, Talbott met Merton and stayed in contact with him in the years to follow. When Merton made his journey to Asia to speak at the Bangkok meeting, he stopped in India and stayed for one month, accompanied by Harold Talbott. During that time, Merton met the Dalai Lama three times. Talbott was present for all three interviews with the Dalai Lama and will present a discussion on Merton's last days and his trip to Asia. The discussion is titled "The 'Almost' Final Days of Thomas Merton: A Conversation with Harold Talbott," and will be held on Thursday, December 7, at 7 PM, taking place at the Clifton Center Auditorium, 2117 Payne Street, in Louisville. All are invited to both events.

For more information on "Kentucky Writers Read Thomas Merton," please call (502)585-9911 or check out the KWC website at www.kentuckywriters.org. For more information on the Harold Talbott discussion, please call the Thomas Merton Center at (502)899-1991.

Books About Thomas Merton

There is a wealth of books, theses, essays, and tributes to Thomas Merton available. Listed below is a very brief selection of books about Thomas Merton, listed alphabetically by author.

Cunningham, Lawrence S. Thomas Merton: Spiritual Master. (New York: Paulist, 1992).

Forest, James. Thomas Merton: A Pictorial Biography. (New York: Paulist, 1980).

Hart, Patrick (ed.) Thomas Merton, Monk: A Monastic Tribute (Garden City: Doubleday Image, 1976).

Mott, Michael. The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984).

Padovano, Anthony T. The Human Journey - Thomas Merton: Symbol of a Century. (Garden City: Doubleday Image, 1984).

Pennington, Basil. Thomas Merton, Brother Monk. (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1987).

Shannon, William H. 'Something of a Rebel': Thomas Merton, His Life and Works. (Cincinnati: St. Anthony Messenger Press, 1997).

Wilkes, Paul (ed.). Merton: By Those Who Knew Him Best (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1984)

A Selection of Books by Thomas Merton

This listing is just a partial selection of works available by Thomas Merton.

Thirty Poems (1944)

A Man in the Divided Sea (1946)

Figures for an Apocalypse (1948)

The Seven Storey Mountain (1948)

Seeds of Contemplation (1948)

The Tears of the Blind Lions (1949)

The Waters of Siloe (1949)

What Are These Wounds? (1950)

The Ascent to Truth (1951)

The Sign of Jonas (1953)

Bread in the Wilderness (1953)

The Last of the Fathers (1954)

No Man Is an Island (1955)

The Living Bread (1956)

The Silent Life (1957)

The Strange Islands: Poems (1957)

Thoughts In Solitude (1958)

The Secular Journal of Thomas Merton (1959)

Selected Poems (1959)

Disputed Questions (1960)

The Wisdom of the Desert (1961)

The Behavior of the Titans (1961)

The New Man (1961)

New Seeds of Contemplation ( 1962)

Original Child Bomb (1962)

Life and Holiness (1963)

Emblems of a Season of Fury (1963)

Seeds of Destruction (1961)

The Way of Chaung Tzu (1965)

Seasons of Celebration (1965)

Raids on the Unspeakable (1966)

Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (1966)

Mystics and Zen Masters (1967)

Cables to the Ace (1968)

Faith and Violence (1968)

Zen and the Birds of Appetite (1968)

My Argument with the Gestapo (1969)

The Climate of Monastic Prayer (1969)

Contemplative Prayer (1969)

The Geography of Lograire (1969)

Opening the Bible (1971)

Contemplation in a World of Action (1971)

The Asian Journal (1973)

The Collected Poems (1977)

Thomas Merton on Saint Bernard (1980)

The Literary Essays of Thomas Merton (1981)

The Hidden Ground of Love (Letters Vol. 1)

The Road to Joy (Letters Vol. 2)

The School of Charity (Letters Vol. 3)

The Courage for Truth (Letters Vol. 4)

Witness to Freedom (Letters Vol. 5)

Run to the Mountain (Journals Vol. 1)

Entering the Silence (Journals Vol. 2)

A Search for Solitude (Journals Vol. 3)

Turning Toward the World (Journals Vol. 4)

Dancing in the Water of Life (Journals Vol. 5)

Learning to Love (Journals Vol. 6)

The Other Side of the Mountain (Journals Vol.7)

The Intimate Merton (Journal Collection)

HOME | THIS ISSUE | ACE ARCHIVES