BY HEATHER C. WATSON

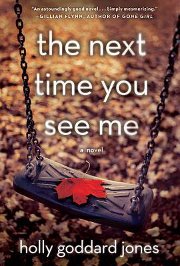

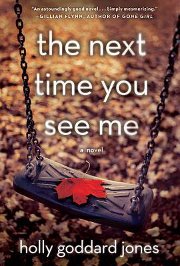

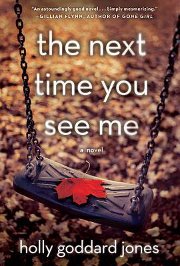

Kentucky native and UK grad Holly Goddard Jones is everywhere these days. In the past year alone, the writer and UK alumna has released her first novel, been featured on BookSlut, recapped an episode of Justified for Slate (like us, she is

We recently spoke with Jones, a professor of creative writing at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro about the novel, writing, dogs, and life.

Ace: Next Time received a fantastic review from the New York Times, and Gillian Flynn called it “an astoundingly good novel.” The last time we talked, you’d just published Girl Trouble, a book of short stories. Now you’ve released an awesome novel through Touchstone (Simon and Schuster). Tell us a little about how you -and Next Time – got here.

Holly: I started thinking very tentatively about the story in late 2007. At that point, I’d been working on a different novel for about a year, gotten a hundred-and-some pages into the draft, and made the dismaying decision to give up on it, because it wasn’t going anywhere. It seemed that the fate of my story collection was very much tied to my ability to produce and sell a novel, and I recognized that I was forcing it, that my investment was in getting the first book published and not in the characters or the plot of the new project. It was a bad time; I felt like a failure. The ironic thing is that I’d won a major writing award that year, the Rona Jaffe, and so it looked on the outside, probably, like everything was going great and I was on the fast-track to good things.

Ace: We return to Roma in the new book. You’ve said before that the town’s name is meant to evoke Roman tragedy, and it’s still true; life isn’t easy in Roma. Like many rural towns, Roma is driven by the hierarchies of school and family. Divisions of class and race are always evident. And, yet, it didn’t feel as though Roma was as much an independent character — driving people’s fate and actions — as it was in Girl Trouble. Was this a conscious choice?

Holly: It wasn’t something I consciously decided to do or not do, but I’m not surprised that’s the effect. Story collections are by their nature driven strongly by a theme. Otherwise, the only connective tissue is the author, and you end up with an anthology rather than a book whose whole is greater than the sum of its parts. So with Girl Trouble, Roma was the connective tissue, the unifying theme, and that meant it had to operate a bit like a character. I do think, however, that the setting in Next Time does drive people’s fates and actions, perhaps even to a greater extent than in the stories. That is, the setting dictates people’s roles, and therefore how they’re able or unable to interact with and impact one another, and that changes the course of the plot.

Ace: The Next Time You See Me is set in 1993. It’s clearly the era of your youth, as you vividly describe the music, the fashion, the hair and other things that a lot of us would rather forget. The Nineties were also a pre-information overload era. Kids weren’t posting their exploits on social media, and news traveled a little slower. It was also a lot easier for conditions like autism (which one or two characters may have) to go undiagnosed. What freedom is afforded to you by setting a novel in the not-too-distant past?

Holly: A murder in a small town is a kind of locked-door mystery, at least thematically. I find that my creativity is stoked as much by limitations as by open expanses of possibility, and so a small town is a rich backdrop for the kind of thing I do. I like the confines, the claustrophobia. But in the age of smart phones, Internet, and 24-hour news, small towns don’t seem so genuinely small anymore. Maybe it was lazy of me, but I just didn’t want to contend with that. Honestly, I’m grumpy about contending with it in real life. I was at a bar the other night, and everyone had a phone sitting out on the table, and everyone kept checking the phone in the middle of conversations. I don’t know how to write about that without making that partly the point, which didn’t interest me a bit in this particular project.

Ace: There is a great line near the end of the novel about the mousy schoolteacher Susanna, who finds her marriage wrecked and her sister’s fate uncertain: “this is what she’d been waiting for: a conclusion so terrible that it eclipsed her everyday unhappiness — so terrible that it showed her the stupidity of thinking all this time that she had to live with it.” This really illustrated a recurring theme: the characters thought they had no power to change the course their lives were on. Would you say the people of Roma are irredeemable, or can they change their paths?

Oh, I wouldn’t say they’re irredeemable, and I might even frame the possibilities a bit differently. To me, it’s more about a kind of culturally imposed paralysis, and whether the characters can find the courage to fight it. Part of the reason I got married as young as I did was the certainty that I’d be ruined or shunned if my boyfriend and I embarrassed our parents by living together. I remember thinking then, too, that an out-of-wedlock pregnancy would be the worst thing in the world that could happen. It was a horrifying thought. And so heartbreakingly short-sighted. I’m not sorry about the life I’ve lived, but I wish I could have a conversation with that younger me and convince her to not worry so much. There’s this big world outside of Russellville—or Roma—and all you can do is work hard and try to be good to people. The rest doesn’t matter as much as you think it does. So writing about these characters was returning to that panicked, suffocated state of thinking from years before—that headspace of thinking that it’s worthwhile to be unhappy as long as your life looks how it’s supposed to look from the outside.

Ace: We Southerners love our dogs. We discussed this in our last interview; you noted that your being a dog owner impacted the scene in Girl Trouble where a dog has to be put down. (I hope it’s not too much of a spoiler to say that no fictional dogs were injured in the writing of Next Time.) The book’s two bloodhounds are among the strongest images of the book. There’s Boss, a faithful old house dog, and Maggie, a trained search and rescue bloodhound. Tell us a little about writing these dogs. It felt like the bloodhounds’ work and temperament were studied and well-researched. Did you consult with bloodhound trainers?

Holly: It’s funny—Wyatt’s dog, Boss, was originally a basset hound, and then a former professor of mine, Lee Martin, published a novel about a lonely man whose most faithful companion is an old basset hound. So I made him a bloodhound, thinking there might be something I could do with that later, a way that the dog’s strong sense of smell might complicate the plot. It had even occurred to me that Boss might at some point be able to play the role Maggie eventually plays, but the more I researched bloodhound Search and Rescue operations, the less feasible that seemed. The dogs require a lot of training and a skilled, familiar handler to be of any practical use. I ended up getting help from a couple of handlers with an organization here in North Carolina, Triad Bloodhounds, and they were great. We met in a park on a blistering summer day in 2011, and they took me on a couple of training runs with their dogs, a bloodhound and bull terrier, who were also trained for cadaver sniffing. It wasn’t as magical an experience as I thought it would be, which was not to say it wasn’t a rewarding and illuminating experience. A lot depends on the handler and how she interprets the dog’s tells. The handler would tell me that the dog’s tail was moving differently than it had before he caught the scent, and I just had to take her word for it, because I didn’t see it. So Maggie is a bit of a fantasy compared to the reality as I experienced it. I took some artistic license.

Ace: What’s next for you?

Holly: I’ve written a handful of new short stories, and I’ve started a new novel. I think I’ll probably have another novel draft before I have another book’s worth of stories. The work seems to be finally moving outside of Kentucky, which I guess is inevitable—I was in Ohio for four years, and this is my fourth year in North Carolina.

Holly Goddard Jones will sign her new novel at Morris Book Shop on March 15. She wrote about book signings for Ace in November 2012 ‘With All Best Wishes.’

This story appears on page 10 of the March 14 print edition of Ace.

Click to subscribe to the Ace e-dition (delivered to your inbox every Thursday), and stay tuned for more author interviews and book reviews.