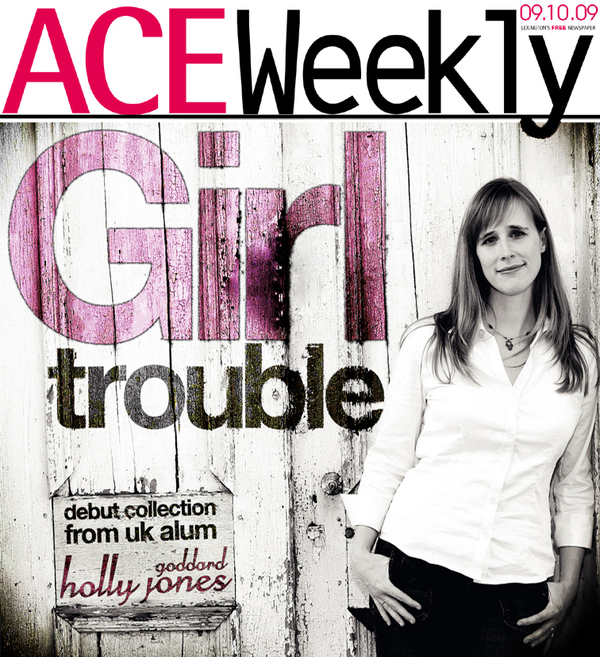

View PDF Ace coverstory interview with Holly Goddard Jones, 2009

BY HEATHER C. WATSON

An interview with author and Kentucky native Holly Goddard Jones feels like a

conversation with an old friend. As Jones discusses her short stories, her dogs, and the state of her tomato plants, she seems more like the salutatorian of your high school class or the girl you wish your brother had married than the winner of the prestigious Rona Jaffe Foundation award for emerging talent in fiction.

If Jones, a 2002 graduate of the University of Kentucky’s creative writing program, sounds familiar to many Kentuckians in both her voice and style of writing, it is because her experiences mirror our own in so many ways. A participant in this weekend’s Kentucky Women Writers Conference, Jones is a native of Russellville, a Western Kentucky hamlet with a population of 7100. She grew up in a blue-collar household where sitcoms like Roseanne were as much a part of the family routine as trips to the public library. She attended Western Kentucky University for one year before transferring to UK, where she enrolled in the creative writing program while her husband Brandon studied Engineering. Her academic career includes a two-year teaching stint at Murray State University.

The short stories in her recently released collection Girl Trouble (HarperCollins, 2009) reflect everyday life in a small Kentucky town with incredible accuracy; her characters work at the local factories, attend hometown festivals, and send their children to state universities. The lilting inflections of their Cave Country accents roll along the page with the spot-on accuracy. It’s easy to believe that these characters, and their creator, are people we know.

When the conversation turns literary, however, Jones sounds far less like the girl next door. As a writer and professor, she presents an acute awareness of her own place in the Kentucky literary tradition; her self-possessed grace particularly unique for a rising author who hasn’t yet reached her thirtieth birthday. When asked about other Western Kentucky writers, she professes a fierce kinship to Bobbie Ann Mason, and finds few similarities to Joey Goebel’s books. She is quick to note that she feels that her works have less in common with the Appalachian literary tradition of James Still or Chris Offutt. She provides snappy yet thoughtful analysis of her fellow Kentucky authors — Goebel’s works don’t focus on “tractors and tobacco juice,” unlike many stories of the state, while Offutt creates an “almost magical” world, and she notes that the tight-knit network of Central and Eastern Kentucky writers doesn’t always extend out to their Western brethren. As she discusses the intricacies of her craft and the tradition of local writers, Jones uses the words “respect” and “honor” over and over, clearly expressing that she writes about the Kentucky that she knows and loves.

As a first-year student at WKU, she was asked to read a story by Bobbie Ann Mason. She vividly recalls the experience as a turning point in her writing career: “I didn’t know that you could write a story about Western Kentucky and people would want to read it.”

A decade later, Jones says, she teaches Mason’s Shiloh in her own creative writing classes at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro, where she is an assistant professor.

As a UK student, she studied under the poet Nikky Finney, the fiction writer Kim Edwards and Kentucky Poet Laureate Gurney Norman. Less than a decade after her matriculation, she will team with Finney, whom she considers a mentor, in conducting writing workshops at the Kentucky Women Writers Conference this weekend.

Edwards, the UK writing professor and best-selling author of The Memory Keeper’s Daughter, has called Jones “a strikingly gifted young writer” who “turns a clear but compassionate eye to the nuances of small-town life.” Those who knew Jones during her undergraduate years recall a talented and hard-working young woman with a knack for precise fiction.

Says Mack McCormack, Publicity Manager of the University Press, “Holly interned in the marketing department at The University Press of Kentucky virtually her entire time as an undergrad at UK. As such, she did a little bit of everything, but her real strength was always writing. We’ve had a few good interns over the years, but she’s one of the best who has come through since I’ve been at the press.”

On her blog, Jones recalls her student days in Lexington, where she and her husband paired the typical struggles of undergraduate students with those of a young married couple. An extravagant date night, she says, would be dinner at Belle Notte on Nicholasville Road, where “a ten dollar pasta entrée would provide two more meals’ worth of leftovers,” followed by a walk through Joseph-Beth, where he would encourage her to buy books they couldn’t afford. (Her reading at Joseph-Beth is scheduled for September 9, 2009)

Jones’s own experiences and struggles as an “everyday Kentuckian” ring true in her fiction. The town of Roma, the setting for Girl Trouble, is fictitious, but is written as a part of Logan County, from which she hails. When asked whether her characters’ experience is uniquely Kentuckian or more universally that of blue-collar small towns everywhere, Jones responds, “I only have experience living in small towns in Kentucky,” she states.

While she suspects that Roma isn’t all that different from small towns in, say, Ohio, she says that there is certainly a Kentucky vibe to her fictional town. “Maybe it’s tobacco, or maybe it’s the Southern accent,” but the experience is certainly Kentuckian.

Like William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, Roma is a fictionalized version of Jones’s hometown. When asked how closely Roma resembles Russellville, she muses “I couldn’t say this is really Russellville. It’s larger than life.” She goes on to note that Roma has a heightened sense of the tragic, with individual characters encountering more extreme situations than a small town usually produces. She bestowed the name Roma upon her fictitious town, purposely invoking classical tragedy which she says “just happens to be in a small Kentucky town.”

While some of the stories in Girl Trouble may seem familiar to readers familiar with the scandals and intrigues of small-town life, particularly that of Western Kentucky, Jones insists that the stories aren’t “ripped from the headlines” in the style of a television police drama. While she acknowledges that “you subconsciously absorb the stories around you,” she is quick to point out that most of the heartache occurring in Roma –a town in which sexual and interpersonal relationships are fraught with power struggles, strife and despair—does not stem from real-life events. She bristles when describing a Publishers Weekly review which called her story “Life Expectancy” the story of a high school basketball coach who impregnates one of his female players, “informed by the tabloids.” She says that she often attempts to shy away from writing fiction that is directly inspired by local events.

Local events are, however, undeniably at play in the parallel stories “Parts” and “Proof of God,” which detail the rape and murder of a Western Kentucky University student. The stories echo the brutal fate that met WKU student Katie Autry in 2003. Jones acknowledges that Ms. Autry’s death was a springboard for these stories. She says that she was haunted by Ms. Autry’s story: “I couldn’t let it go. I was having nightmares about it. The way for me to make sense of it was to write about it.” She began the process by writing the story Parts, which tells the story of a mother dealing with the aftermath of her daughter’s murder in what Jones calls a traditional storytelling approach. “If something that horrific happens to your family,” the author asked herself, “how does it affect the rest of your life?”

While working on her M.F.A. at Ohio State, Jones says that she was challenged by her creative writing professor, Lee Abbott, to reconsider the perspective of the Katie Autry story. Professor Abbott encouraged his creative writing students to tell a story from a difficult viewpoint; Jones chose to tell the story from the perspective of a rapist and murderer.

As she delved deeper into the second story, “which became “Proof of God,” she says that she began to diverge from the initial inspiration of the Katie Autry story. She removed the elements of class struggle inherent in the actual crime and began to look at the psychological profile of her characters. This result, Jones says, is far preferable to writing a direct “true crime” account. She also notes that she doesn’t want to sensationalize actual events of the region out of respect for her hometown. “It’s important for me to honor where I’m from,” she notes. “I want people to be proud that someone local wrote a book. I would be heartbroken if people thought it was a stereotype.”

Far from a stereotype herself, Jones is well-versed in high and low culture, a juxtaposition which she says that she intentionally includes in her work. She grew up reading true crime and genre fiction, influences that can be seen both in her unflinching portrayal of crime scenes and in the rough justice exacted by Roma’s crooked cops and easily swayed prosecutors. She is similarly immersed in classic literature; Plato, Descartes and Shakespeare are directly discussed in Girl Trouble. As she describes a household which recognized the innovation of such television shows as Roseanne and Murphy Brown while also instilling a voracious appetite for books, it is easy to see the basis for Girl Trouble characters such as a Plato-quoting truck driver or a mother who frames her life’s tragedies in the context of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, as well as those characters who select late ’80s hair metal or Johnny Cash songs as the appropriate soundtracks to their daily activities.

Jones says her own modern literary influences include William Faulkner, Joyce Carol Oates, and Andre Dubus. The inclusion of an Epigraph story in Girl Trouble, she says, is a direct homage to Faulkner. The well-versed reader will certainly also see Faulknerian influences in the fictionalized town of Roma, from the characters’ realistic dialects to their moral dilemmas. Jones notes that the Dubus short story called “A Father’s Story” moves her to tears and strongly influenced her story “Good Girl;” both stories deal with the sacrifices that a father makes for his child.

Like her literary role models, she says that she has never shied away from “big stories” about right and wrong. As such, she creates a world in which her characters create bright-line dichotomies for acceptable behavior. The people of Roma strongly abide by strict codes of morality. They self-identify as good or bad men, and assess their friends and neighbors by the same stringent code. Women are classified as “good girls” or “bad girls,” with the accompanying moral judgment those titles connote. The people of Roma live hard lives and their fate often feels preordained, yet they possess a certain quiet dignity, even in the most desperate situations.

Jones’s strength lies in setting subtle scenes which provide a glimpse into their character: A man’s treatment of his dog symbolize his inner strengths or weaknesses, a father stands by his criminal son to the detriment of his own happiness, and a teenage girl must choose whether she wants to be part of a seedy crowd. It is at first difficult to reconcile Jones’s smart, feisty girl next door persona with the haunting stories of death, loss and morality of the collection. She best explains this paradox in describing the impetus for the story “Good Girl,” a story in which a pit bull has bitten a child. The character Jacob, the father of the dog’s owner, feels extreme attachment to the dog, but makes an unsentimental choice. Initially terrified by her in-laws’ pit bull, Jones says she began the story as a tale of terror. Upon becoming a dog owner herself, she became fiercely loyal to her dog in what she calls an “almost religious conversion.”

This personal experience created a dramatic shift in how she crafted the Jacob character, Jones recalls. “I wrote more effectively because I could feel.”

In writing about the Kentucky life that so many of us feel or know, Holly Goddard Jones spins a smart, sassy and empathic yarn. ■

Girl Trouble is the Ace Book Club Selection for October (The Club meets first Wednesdays of every month.). Jones will sign Girl Trouble at Joseph Beth on Wednesday, September 9, 2009 and will participate in the Kentucky Women’s Writers’ Conference this weekend.

[amazon asin=0061776300&template=iframe image]

Holly Goddard Jones will be at …

❊ Joseph-Beth Booksellers Wednesday, Sept. 9, 7pm

❊ Kentucky Women Writers Conference Friday, Sept. 11, 10:30am to 11:45am

Text and Subtext Fiction Workshop 1 (Lexington Public Library), 4:30pm to 5:45pm Reading with Nikky Finney (Lexington Public Library)

❊ Kentucky Women Writers Conference Saturday, Sept. 12, 10:30am to 11:45am

Text and Subtext Fiction Workshop 2 (Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning)

❊ Kentucky Book Fair (Frankfort) Saturday, Nov. 07

***

The first selection for the Ace Book Club in October is Girl Trouble, by UK Alum Holly Goddard Jones. Longtime readers know, Ace has always been about celebrating great writing and great writers. Holly is a graduate of UK and received her MFA from Ohio State University, where she studied with Erin McGraw

(Erin taught workshops at the Ohio/Kentucky/Indiana Writers’ Roundtable, which Ace ran with author Ed McClanahan back in the 90s. Small world.)

The Ace Book Club will meet the first Wednesday of the month. October 7 will be the first meeting. The first meeting will be at Charlie Brown’s on Euclid at 6pm (big sofas, surrounded by books).

Ace Event Invites are always posted on the Ace Facebook Fan Page. (www.facebook.com/AceWeeklyFans) We hope the Club will develop a core group of Regulars — but unlike many Book Clubs, Readers will be welcome to drop in and drop out based on that month’s selection — which will usually be related in some way to Ace editorial content. By definition, that will usually mean relatively new work (because that’s usually what Ace covers).

We know not every book will interest every Ace Reader — some Readers might enjoy a great food book, and others might come for searing non-fiction social commentary.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Holly Goddard Jones Recounts her Book Tour So Far Ace October 4, 2009

TV or not TV: Holly Goddard Jones Remembers Dixie Carter Ace May 13, 2010