View PDF page 6, Ace April 26 2007. ESH Cemetery stories

[two_third]Open Forum

Inviting the Public to the ESH Process

By Bruce Burris

A few years ago while looking for a space to place a community garden I came across a small overgrown enclosure surrounded by a broken chain link fence directly behind the Hope Center. That space contained the unmarked and mixed remains of some 4,400 people who had been patients at Eastern State Hospital between 1820s and 1950s. Sometime after this, and with the help of advocacy organizations such as the Fayette County Cemetery we began the Eastern State Hospital Club. Its purpose initially was to advocate in the most basic of ways for the creation of a dignified cemetery space, but since the founding of the club, two things have occurred which have added to our initial mission. The first was the gradual realization that there were many more remains scattered around the original grounds then we thought. As it now stands in addition to the 4,440 who have been reburied (some for a third time) there may be as many as 10,000 plus buried between Fourth Street and what is now LexMark.

It is our concern that those of us in the community will have little opportunity to express our ideas on what might become of that property and therefore we are organizing what we hope will be the beginning of a number of community conversations around this topic. The information and ideas for land usage recorded during this meeting will be forwarded to policymakers at LFUCG and in Frankfort.

Envisioning the Future for ESH

Thinking Big, Thinking Wide

By Jim Embry

Over the past several months a variety of people have been bumping into each other at the idea Mecca, also known as Third Street Stuff (3SS), and sharing ideas about the future use of Eastern State Hospital. Creative ideas have a way of flowing in a place like 3SS where color and love reverberate. This article is an attempt to distill these ideas about ESH into some kind of coherent framework. So welcome aboard.

Systems thinking

We agreed that systems thinking, a necessary ingredient for developing a vision for sustainable cities, is written about often but is in short supply as an everyday planning tool. Wrapping systems thinking around the question of ESH would require that we (among many things) look at the closed Russell School building, the soon to be closed Johnson School, the vacant Lexington Mall and also the closing of the Veterans Hospital and see how the future use of these large structures fit into some integrated plan that would enhance our sustainability as a city.

Community involvement

Community involvement is another necessary ingredient for sustainable development. This conversation and visioning about the future of the ESH should involve staff members, community residents, business owners, youth, government & educational personnel and community agencies. So often just the

movers and shakers sit behind closed doors and decide on the future of our city without fully understanding that moving from a single red rose to a bouquet of roses involves being very trans- parent and inclusive of all the various community partners.

Eco-Arts Village

Since many of us were art and eco geeks, we were most excited about the concept of ESH becoming an Eco-Arts Village. Such a place would provide a community experience that is both socially and economically viable as well as ecologically sustainable with a focus on the arts, organic horticulture and a healthy environment. We envisioned that one of the buildings would become an artist village and would include interior and exterior gallery spaces, a small community theatre, residential apartments for artists, artist’s studio space, artisan retail shops, an outdoor amphitheater for performance events and gatherings. As an example of social entrepreneurship this Arts Village, including all art forms, would be economically sustainable and artistically inspiring.

greenhouses would develop a small scale farm, communal orchards, an associated small-scale wastewater treatment plant that directs treated sewage effluent from the Village to agricultural use, rain gar- dens and storm water collection points, a composting facility that also produces liquid fertilizer, a mushroom farm, a farmer’s market and grocery. One of the buildings could become a public school with an entrepreneurial eco-arts curriculum. With various size housing units residents would be encouraged to work on site in the horticultural and art businesses…or live where they work.

Caring for the Earth, caring for people, living creatively—together, this Eco-Arts Village could become a national model for creating sustainable communities.

Jim Embry is a member of the Sustainable Communities Network.

The Lunatic Asylum

Lexington in the Age of Cholera

By Terry Foody

Almost 200 years ago, citizens in Lexington envisioned a hospital to care for the poor, disabled and mentally ill. This Lunatic Asylum (Insane Refuge) has been a part of Lexington all this time, and is now Eastern State Hospital.

The treatment of the mentally ill in the 1800s was limited by the theories and practices of the time. There was a tendency to institutionalize those with birth defects, epilepsy, dementia, and “old age feebleness.” Many of the patients were indigents with no family or friends.

Patients were occupied in domestic and farm labor. This “would “arouse dormant or wayward energies to consistent and vigorous action.” (Dr. WS Chipley’s Report to the Commonwealth 1858, 1859). “Command you your mind from play every moment in the day.” (UK Special Collections.)

With a low cure rate, many patients admitted to the hospital eventually died there. “Acclimating disease” with symptoms of diarrhea and low grade fever was a chronic problem But Asiatic Cholera was the true grim reaper. When the Cholera Epidemics struck Lexington in 1833, and ‘49, 100 victims were from Eastern State. Environment may have been a big factor. There was a mingling of the drinking water source with the common sewer under the building. Correction of this diminished mortality.

In the 1849 Lexington newspaper, the cholera deaths were divided into City Wards and then the Lunatic Asylum. Were these patients not seen as part of the general population? (They came from different counties and states.) O were there so many deaths at the Asylum that it warranted a separate report? Who gets marginalized in a disaster/epidemic? In Katrina, it was the poor and chronicaly ill.

Recently, there was a reburial at Eastern State of eleven bodies from an unmarked unknown mass grave. How easy it would have been to end up like this. Anyone can become indigent, alone, mentally ill, institutionalized. With a pandemic flu, mass, unmarked graves might be a possibility. Disease is a great equalizer.

We learned in 9/11 that every part of a person has dignity and importance. Identification of remains is crucial to survivors.

The scientists who studied the Eastern State bodies found clues about the person’s life from bones and fragments. What will happen if the property is developed with no thought to other possible graves? Is this really a safe refuge/resting place for the insane?

We are responsible to preserve graves and deceased information for those decedents who will seek and have no one to ask.

(Terry Foody, RN, MSN, Certified Clinical Research Coordinator)

Notes:

*handwritten quote on back of Chipley’s report.

Other sources:

Lexington Observer and Reporter, August 18, 1849.

White, Ronald F. Dialogue on Madness: Eastern State Lunatic Asylum and mental health policies in Kentucky 1824-1883. UK thesis, 1984. Ranck, George W. History of Lexington KY 1872.

Preservation

Other State Hospitals and their Futures

By Phil Tkacz

The situation in Lexington is part of an ongoing national problem. After the institutionalization that started in the 1980 many states found no need to keep most of their mental institutions open, for better or worse. Unfortunately many were historic buildings that sat vacant for many years and recently they are falling victim to redevelopment. In some cases, the hospital cemeteries are preserved since they were marked, unlike Eastern State Hospital. This makes the situation in Lexington all the more important for preservation since there are possibly as many as 10,000 patients buried on the grounds with no location known for most and it is the second oldest state-run psychiatric hospital in the nation.

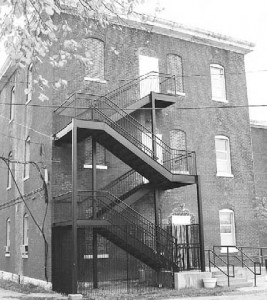

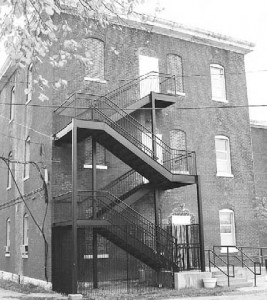

grounds during trench-digging for a water main. Photo by Phil Tkacz

In Massachusetts, at the former Danvers State Hospital, the Danvers State Memorial Committee has worked with the state and developers to preserve the graves of over 700 former patients buried there. Although most of the historic buildings were demolished to make way for condos, there is a memorial on the property. It is an ongoing project statewide at most of the hospitals that are no longer used and facing redevelopment. Manteno State Hospital in Illinois closed in 1985, the state turned the northern half of the property and building over to the Veteran’s Administration, who maintains the only known cemetery on the site. The southern half was sold to a developer and has preserved some of the buildings.

In South Dakota, at the former Hiawatha Insane Asylum for Native Americans, the cemetery there had a golf course built where 133 former patients were buried. Indianapolis, Indiana is home to Central State Hospital that closed in 1994. Shortly after, the state sold the property to the city, which has been unable so far to attract developers to the site due to unmarked graves and buildings full of asbestos. A reuse committee was formed with members from the city, neighborhood groups and other citizens. Al though not much progress has been made, it is an example of cooperation.

There are many other examples of these hospitals and what they stood for ending up lost to bulldozers for Wal-Marts and condos, and in most cases, residents that live in the cities where they are have no say in the development. Kings Park Psychiatric Center in Kings Park New York, people living in the neighborhood prefer the mostly vacant building and greenspace, instead of the apartments and shopping center that has been proposed many times.

There are too many places to list here, but Eastern State Hospital and Lexington could be a good example for the nation of giving an old state hospital a new use while preserving historic buildings and the resting place for many former patients who were forgotten.

Phil Tkacz has researched what advocates with other state hospitals cemeteries have done. Nationally there are a number of state hospitals located on what is now valuable property which have closed. Most contain cemeteries in various states of disrepair- but ESH cemetery seems unique in—the potential high number of remains scattered across the grounds—and because there are few hosptital records of grave markers.

African American Burials

Fayette County’s Storied Past

By Yvonne Giles

The history of African American burials in Lexington, Fayette County naturally dates back to the beginning of the county and city. Those who were enslaved were buried on the same land that they worked. All we can do is guess at where their remains might be on the once large farm. Were they buried in the family plots or in unidentified sections marked by fieldstones which may have been moved or by cedar trees which may have been cut down. It is a sense of loss not to know where they were buried. We know that there are over 200 pioneer burial locations in Fayette County thanks to the work of the Fayette County Cemetery Trust, Margaret Kenneshon, former county attorney, and others who have documented their existence.

In the city, those who died were buried in public burying grounds located first on Main Street, then Bolivar Avenue and finally on Broadway. Research in to this history of publicly owned cemeteries revealed in the February 1878 minutes of the Board of Councilman, that the Keeper of the Workhouse was given the responsibility for “the internment of the dead both white and colored.” He was to bury all White persons in Section A in a prescribed manner and all Colored persons in Section B in the same manner. The cemetery was known as Mt. Vernon City Burying Ground on Broadway. What relatives may have been buried there, what became of their remains when the property was sold for the development of the tobacco warehouse?

The Old Presbyterian Cemetery once located in the block between 6th and 7th and Limestone and Upper Streets was one of the sites which accepted the burial of African Americans. When the property was sold, the state required that all remains be removed to another burial location. Those who had relatives claimed the remains and primarily reburied them at the Lexington Cemetery. About 300 African Americans were moved to the Benevolent Society No. 2’s cemetery located on 7th Street according to newspaper accounts of 1889. Some were identified with markers and others not. Were some relatives among those placed in the mass grave?

This cemetery was formed in 1869 as a four acre site which was expanded to eight acres in 1875 by the society which had been founded in 1852 to “care for the sick, bury the dead and perform other acts of charity.” At one time the cemetery was outside the city limits surrounded by the land belonging to Dr. Elijah Warfield, John Fowler, James Baker, David Sayre and others. Although legally known as Benevolent Society No. 2 Cemetery, it was called No. 2 Cemetery, Colored People’s Cemetery and finally African Cemetery. The cemetery, owned and managed exclusively for African Americans, accepted burials from its inception until 1976; it holds well over 8,000 burials documented through death certificates. 1,200 gravestones have survived the years of vandalism.

The second cemetery owned and managed exclusively by and for African Americans was founded in 1907 by fourteen males who named the site Greenwood Cemetery and Realty Company. The name was shortened to Greenwood Cemetery in 1942 and changed to Cove Haven Cemetery in 1985. The site covers sixteen acres and is still actively accepting burials.

It may be difficult for others to understand the feeling some of us have when we are searching for the final resting place of our forbearers. It is the same feeling a mother has when she knows all of her family is not safe at home in their beds.

“Yvonne Giles is a community activist and Director of the Isaac Hathaway Museum. She is writing here about her experience with the African American cemeteries in Lexington, and though not specifically connected to the ESH cemetery—the concerns and indignities are parallel. Yvonne is a member of the ESH Cemetery Club.”

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]Eastern State Hospital Informational Meeting

Lisa Sanden, President, Fayette County Cemetery Trust

Fayette County Cemetery Trust is a not-for-profit organization, dedicated to identifying, protecting, and preserving our private family and church cemeteries. Efforts to preserve the unknown amount of bodies buried on Eastern state are in-line with our organization’s goals.

residents.

The Public meeting in May will provide further, more detailed, explanations regarding the past of this historical site and what the future holds.

Eastern State Hospital Cemetery Club is taking suggestions to create a community and family based proposal as we work with the Local and State Governments deciding the future of this Historic Hospital.

Tuesday, May 8, 2007

6:30pm

Central Library,

1st floor Conf Room

The Research Update

By Mary Hatton

The Fall of 2006 I joined the ESH Cemetery Club. Being a retired Registered Nurse with 20 years of patient care at Eastern State Hospital and a researcher. I decided the most productive way to help the ESH Cemetery Club was by researching for names of patients who lived, died, and were buried at ESH or were buried elsewhere.

Research has been made possible through the efforts of many people, such as patient relatives, friends, and other interested persons who want to see the cemetery and building on the historic register preserved. The Eastern State Hospital research was taken public on the Fayette Co. KYGenWeb because Eastern State Hospital is located in Fayette County.

In December 2006, Naming the Forgotten – The Eastern State Hospital Projectbegan as a special project within the KYGenWeb (http://www.rootsweb.com/~kygenweb/esh/). Working with various records, our goal is to identify those who lived and died at the hospital before 1958. Prior to the state mandated registration of deaths in 1911, records pertaining to these individuals are scare. Naming the Forgotten: the Eastern State Hospital Project is assisting the Eastern State Hospital Cemetery Club by sharing information found regarding persons interred at the hospital cemetery.

Research is being conducted using public records such as death certificates, newspaper obit-uaries, newspaper court commitments, census, mortality indexes, circuit court commitments, letters, Find-A-Grave, ESH annual eports, ESH deeds, pictures, and medical records given by families. Also, found on the website are Eastern State Hospital Tables and Statistics 1907-1909 &1958 Division of State for Asylums.

Sometimes items are discovered by accident. I was in Fleming County at the courthouse getting circuit court commitments when the resident genealogist brought out two books that she saved from the trash. One book contained the Legislative Annual Report from the State of Kentucky ending October 10th, 1879 & the second book contained the Legislative Annual Report from the State of Kentucky ending March 31st, 1881. Both books had the names of all patients who were in ESH, their usual residence, and means of support. Court Commitments have been found in both circuit court and county court offices in Bourbon and Harrison Counties.

Relatives and interested persons now have a website: (http://www.rootsweb.com/~kygenweb/esh/), a contact, and a means to obtain medical records. Relatives can contact me for nformation to obtain medical records for both ESH & the Old Kentucky State Hospital that closed in 1977.

One relative added the ESH Cemetery to Find-A-Grave. There ave been 295 patient names added to Find-A-Grave to date.

[/one_third_last]