Ace September 1994

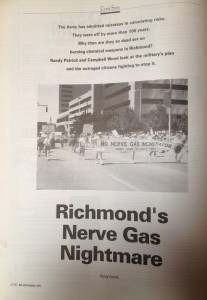

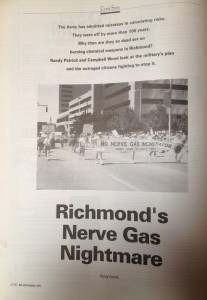

Richmond Kentucky’s Nerve Gas Nightmare

by Randy Patrick

David Easter, public affairs officer for the Blue Grass Army Depot, pulls up beside a guard house and exchanges friendly banter with the guards before driving on.

“We’ve just entered a higher security zone,” he says. “I have a duress code with those guards. What I say or don’t say signals what my situation is. If I’m in trouble, a SWAT team will close in. It’s understood that I’m expendable.

He stops the car. “This is as far as we go,” he announces. In front of us are two six-foot chain-link fences, each topped with concertina wire.

Outside the fences, every fifty feet, are the same large sign prohibiting entry. They warn in bold letters: “USE OF DEADLY FORCE AUTHORIZED.”

This is where the chemical weapons are stored.

Easter points to an adjacent field. “Over there, if it ever gets built, is where the incinerator will go, and the fencing would be extended around it.”

***

For ten years, the Army has used the threat of unstable weapons to try to persuade residents and lawmakers to support its plan to build a half-billion dollar incinerator complex on site to burn the 70,000 nerve gas rockets as well as an undisclosed number of artillery shells containing blister agent or mustard gas. A recent discovery by a group of scientists hired by the Army to review its plan reveals that the threat of continued storage of the weapons may be greatly exaggerated.

According to the Army’s 1993 Mason Report, the stabilizer in the M55 rocket propellant could begin to deteriorate within 17 years, possibly resulting in spontaneous combustion of the fuel. But last month, the Army admitted that its estimate was off by more than a hundred years.

What happened, according to Mark Evans, Army spokesman for the Chemical Demilitirization Program, was that the author of the report substituted days for weeks in determining the rate of degradation. He said the mistake occurred because data from the manufacturer of the fuel contained no time element. “He assumed it would be in days instead of weeks,” Evans said.

Craig Williams of Berea, leader of the local citizens group Common Ground, and spokesman for the Chemical Weapons Working Group, a national coalition opposing the Army’s plan, thinks the numbers were cooked to get the results the Army wanted. The Army wants Congress to approve fnding for incinerators at the Blue Grass Army Depot and seven other bases where the weapons are to be destroyed. A decision is scheduled for later this month.

Williams said that when the scientists discovered the rror and opponents learned about it, the Army made an effort at damage control by releasing a statement saying that it had miscalculated the deterioration rate.

“Either they purposely misrepresented the truth or they’re grossly incompetent,” Williams said. “That’s the choice.”

Evans dismissed the accusation and said Williams was wrong in assuming that it would have been to the Army’s advantage had the mistake gone undiscovered because the viability of the rockets was not considered in deciding to move ahead with the program. A statement released August 15 1994 by the National Research Council’s Committee on Review and Evaluation of the Army Chemical Stockpile Disposal Program said the risk assessment in its February report to Congress was based mainly on the risk of external events such as airborne crashes or tornadoes at the storage site…”

“The risk of detonation of M55 rockets from spontaneous ignition of M55 propellant was never the basis of the committee’s recommendations for promptly proceeding with the disposal program. Consequently, the new information regarding propellant stability does not change the recommendations of the committee’s February report,” the statement read.

However, the Army’s own testimony earlier this year contradicts that statement.

Testifying for the feasibility of the incineration plan before the Senate Armed Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Nuclear Deterrence, Arms Control and Defense Intelligence on April 26, 1994, Assistant Secretary of the Army Robert M. Walker said the Army’s recommendations were based on assessment of the total risks, both external and internal. “This is particularly important with respect to M55 rockets, which are the most susceptible munitions in the stockpile to developing leaks or other problems which potentially could affect continued safe storage,” he said.

Dr. Carl Peterson, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and former chairman of the stockpile committee, testifying before the same subcommittee, said that the rockets could reach critical levels of instability between the years 2002 and 2019. If the stability of the reactants weren’t a critical factor in the final recommendation, why would Dr. Peterson conclude his testimony with: “Ignition of a rocket in an igloo containing several thousand rockets would certainly result in substantial release of agent; it is an event to be avoided at all costs.” Peterson made similar remarks during a public meeting in Madison County earlier this year.

Williams said it is obvious that the possibility of a catastrophe caused by spontaneous burning of the rockets was being used as “the fear trigger” to get what the Army wants.

The Army may get its funding soon. Money for startup costs is included in the 1995 Defense Authorization Act, which has been approved by Congress and is awaiting President Clinton’s signature. The appropriations bill has passed the House and Senate and is expected to go to a joint conference when Congress returns from Labor Day recess.

The federal government plans to spend $9.8 billion to destroy more than 30,000 tons of chemical weapons at the eight storage sites in the continental United States. Army officials have contended that safety, not cost, is its principle concern.

The Army’s studies conclude that its incineration program is much safer than continued storage at every site except Richmond, where the risks are about the same. But the track record of its prototype facility on Johnston Atoll in the Pacific Ocean shows that the program is fraught with problems.

Since the Army initiated the burning of chemical weapons at Johnston Atoll in 1990, the facility has been inoperable half the time due to technical difficulties. During 500 hours of testing in 1992, the plant was shut down 32 times. Also that year, it was closed for a month due to a fire. The incinerator has been shut down since March of this year when a malfunction resulted in a leak of an undetermined amount of nerve gas into the atmosphere. A smaller prototype at Tooele Army Depot in Utah has experienced similar problems.

Opponents of the Army’s program say it is doubtful that it could meet federal Environmental Protection Agency standards for safe operation. It is even less likely that the Army can meet the stringent permitting requirements set by the Kentucky General Assembly in 1992. Thelaw requires the Army to demonstrate that the facility can destroy 99.9999 percent of any substance to be treated. State Rep. Harry Moberly Jr., D-Richmond, said he doesn’t think the program can accomplish that level of efficiency. “The law may result in a lawsuit by the federal government,” he said.

Our attorneys have reviewed this bill with a legal challenge in mind, and it is their opinion that the bill is defensible,” said Charles Bracelen Flood, spokesman for the anti-incinerator group, Concerned Citizens of Madison County.

The Chemical Weapons Working Group wants the Army to dismantle the weapons and store the chemicals and munitions separately until a safer alternative can be developed. Several alternative methods of disposal that do not result in potentially dangerous emissions have been tested and offer hope for a better solution.

“Early on,” said Williams, “we realized that just opposing the incinerator locally was passing the buck. And no matter where you burn this stuff, it’s going to get into the food chain. Whether it’s through chicken in Arkansas or potatoes in Oregon, Americans are going to end up with toxic dinners. So instead of the elitist posture of ‘not in my backyard,’ we took the more inclusive approach of ‘not in anybody’s backyard.”

Dismantling the weapons would meet a congressional requirement that the weapons be “demilitarized” by 2004 in accordance with the Chemical Weapons Convention. But Charles Baronian, the highest-ranking civilian in the Army’s chemical disposal program, said earlier this year that separating the chemicals from the munitions would create hazardous wastes that, by law, must be disposed of within a year.

“I don’t know what he’s talking about,” said Vanessa Verge, a Lexington environmental attorney who represents the citizens groups. She said she has never heard of such a law and thinks he may be referring to some requirement in the Army’s permit. “He may think those obligations are written in stone, but they’re not,” she said. “There are provisions for waivers for almost every deadline that’s contained in environmental laws.”

Incinerator opponents are prepared to go to court to stop the Army if necessary, and some Kentucky officials have said the state may also sue. In addition to litigation and other difficulties in getting its permits, the Army could face massive protests and civil disobedience if it continues its present course.

Williams said the groups do not want to delay disposal of the weapons or cause the Army to miss its 2004 deadline. He said a contingency plan made public in 1985 shows that the Army could dismantle the munitions at Blue Grass Army Depot within a year, reducing the risk of continued storage to zero.

“What we’re saying to the Army is ‘You can get there using our approach, but you can’t get there using your approach. We’ll have you in court for three fucking years.'”

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

The Chemical Arsenal at the Bluegrass Army Depot Ace September 1994