A Local Patriot’s Pride

By Kim Thomas

When we were kids and went on vacation, the inevitable songs of summer would be played repeatedly on the radio. Each year, there was a song that my father absolutely couldn’t bear to hear without letting us know how he felt, saying, “Well, now that’s a hell of a song!” The first time I remember this happening was the year Eric Clapton recorded “I Shot the Sheriff,” and my Dad would drolly say, “’I shot the sheriff, but I didn’t shoot the deputy!’ Now that’s something to be proud of!” Several years later, the song, “Dirty Laundy” would play and he’d say, “’Kick ‘em when they’re up, kick ‘em when they’re down’ now that’s a helluva song...something to be proud of!” We always were amused by his dogged dislike of rock-n-roll, but as we grew older we realized he had a perspective that we could never quite grasp. He had a view of America as a free country whose citizens should respect their independence and embrace artistic diversity, even if the message was not necessarily one to be proud of.

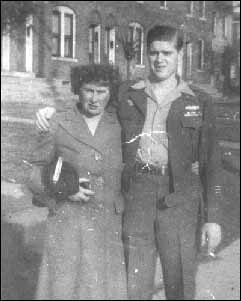

The following letter was written by my father’s WWII army buddy, Walt Freitag. Mr. Freitag sent this to me and my six brothers and sisters on April 7, 1997, the day my dad died, in response to our request for some information about Dad’s army background. Dad had never talked about the war with us very much, but rather instilled in us a deep respect for our nation and the liberty we enjoy. Accordingly, we never knew much about exactly what transpired “over there” until we received Mr. Freitag’s letter. In it, he refers to my Grandmother Thomas (Tommy) and my Aunt Sherry, who lived in Norwood, Ohio at the time. I only recently re-read Mr. Freitag’s account and found it to be not only interesting but comforting. It is my hope that by sharing this letter, that others might learn not only of the sacrifices our WWII veterans gave, but also of their ingenuity and diligence in preserving the freedom we enjoy today. As a daughter of an American soldier who used his many resources to fight for freedom and protect his fellow soldiers, I just have to say, “Now THAT’S something to be proud of!”

April 9, 1997 Wednesday

April 9, 1997 Wednesday

Dear Sons and Daughters of Marsh Thomas,

Margo and I express our deepest sympathy to the entire family for your deep loss.

Thank you for your kind request for information about Marshall’s military service, and our personal relationship through the years. Will do the best I can.

Marsh and I first met at Fort Benning Georgia, where we were both first inducted into the WWII military under what was known as the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP). This was a program we all chose, instead of Officers Candidate School (OCS), because we hoped to remain in college until the army needed its next batch of officers—expecting that the war might last many more years.

After basic training, Marshall and I, along with a number of our newmade friends, were shipped to Heidelberg College in Tiffen Ohio to start an Engineering Curriculum. After just two months we were informed that the entire program was being disbanded, and that our entire group (approx 150) was shipped out to the 102nd Infantry Division then located in Camp Swift, Texas. We all realized then that we had made a bad choice, but those are the breaks of army life.

The 102 was originally a national guard unit made up of volunteer guardsmen from the Ozarks, hence the name, “The Ozark Infantry Division.” Many of the original guardsmen were in their late 30s to late 40s—obviously unfit for combat—which was proven by forced marches which caused many to be discharged or reassigned to lighter duty. Our role was to fill the division with young, physically able recruits who could help bring the division quickly to fighting form. This done, the division was shipped to Fort Dix, New Jersey for additional fine tuning and then through Port of Embarkation (POE) Camp Pendleton, on shipboard to join the fighting in the European Theater.

Our troop ship was the first to sail directly into Cherbourg Harbor where we were off-loaded and went directly into the St. Lo area of France, continuing on, bypassing Paris and through Belgium and Holland. Our first really heavy fighting was in the Aachen area and in the heavily fortified Siegfried Line. After initial losses which reduced some units to less than 20 percent of their original strength, we pulled back, “licked our wounds,” picked up replacements and went right back into action.

Because of the heavy losses, Marsh and I both went from PFC to Staff Sgt. In a matter of hours.

This heavy fighting continued through the Siegfried Line where our division was stretched out to dover a front normally held by three divisions, in order to send our support armor and infantry to help out in “the Battle of the Bulge,” just to our south.

After the Bulge, we crossed the Rohr River, the flat, heavily fortified Rhine plane and up to the Rhine River at Munchen-Gladback, across from the city of Cologne.

Marsh was involved in leading many night patrols into enemy territory, always carrying out his assignments with a minimum of loss of his command, and brought back invaluable information and captured enemy for interrogation—information for our officers’ strategic use.

It was in those times, and especially when we were in holding positions, that Marsh and I were inseparable. We dug in together, often with some of the fanciest foxholes in the company. During freezing weather, the ground was frozen hard, making digging nearly impossible. One day Marsh came back from a trip to the “line” carrying a handful of blocks of TNT which he had “requisitioned” from a nearby group of Engineers (who had left a box unattended). We used the TNT to blast the frozen crus so we could more quickly “dig in” when we were suddenly caught by “incoming freight” (artillery or mortar fire).

We always covered for each other—who can count the number of times or ways?! This went on until one day, while crossing the Rhine Plain, we came up to a large farmstead consisting of a large house and hay barn, connected by a series of walls and adjacent buildings which formed a large courtyard. Suddenly the buildings were hit by a series of well placed “88” direct firing artillery. Those of our company inside the building were shrapnel and broken bricks. I have no idea how many were lost, killed, and wounded that day—before and after that death trap.

We all acted somewhat independently to take care of our men, getting as many as possible to cover. In the process of saving his men, Marsh was hit by a spent artillery shell and several pieces of broken brick.

He was one of the first I dragged into the basement of the house, patched him up as best I could, gave him a shot of morphine, broke open a wine cellar and left him awith a bottle of wine in one hand and a bottle of Dujurdin Imperial Cognac in the other. I never saw him happier!

There is no doubt that his earlier quick action saved the lives of 8 to 10 of our company. For that day, he was awarded the Purple Heart Medal, and I understand that he also received a Silver Star Medal for the action. I had to leave him at that point, because there were a number of other pressing matters to attend to—like bringing order out of chaos, and continuing the battle with the few we had left to fight.

Marsh was patched up at the aid station, and was shipped back to Paris where he was given a number of tests to determine his eligibility for West Point. He chose West Point rather than return to his outfit and was subsequently sent back to the States.

At West Point (according to a letter he wrote me), Marsh was discharged from the military services for a short time so they could swear him into West Point as a cadet. During that brief period as a civilian he promptly did what any young red-blooded American (who had been through the hell he had experienced) would have done; he told them he had changed his mind—and went home with a promotion to the rank of “civilian first class.”

After the war had ended and I had been discharged, we continued to remain close friends, writing frequently. He visited us in Iowa during summers while we were in college—Marsh trying to teach my Dad how to swing a golf ball and Dad paying him off in beer—always “the best idea you’ve had all day.”

In turn, I hitch hiked out to Norwood twice to visit Marsh and get to know Tommie, Jane and Sherry (I fell in love with Sherry’s photos when Marsh and I were sitting in foxholes reading each other’s letters). By the time we got back, Sherry had 2 or 3 kids, so we just went down to the tavern for another case of Barbarrosa Beer. By the time Tommie got home from work that evening, we had plastered the ceiling with Barbarrosa Beer labels. Tommie took one look at the ceiling, laughed and got us each another beer. Later that week Arnold (Shorty) Reisen arrived and we went out to play golf, and of course consume a few beers (payoff from the golf games). These were fun times, and we finally settled down to our studies, got married, and started making babies (and you’re evidence of what happened).

We saw each other twice after that—once when we were living in Michigan and Marsh and Pearl had moved into a brownstone in Chicago. Don’t know which of you is the oldest, but Margo remembers holding you during that visit.

The other was in 1969 while you were living in Covington, where we stopped in for a two hour visit while I was driving through on a business trip to Louisville. Marsh moved several times and so did we.

With no address, we completely lost track until 1991 when I sent a letter to Arnold Reisen c/o Ohio State U, requesting they forward it, eventually, to Marsh.

He did, and Marsh did make it to the 1992 Ozark reunion and a visit to our house here in Washington. From there, you know the rest of the story.

The last time we saw Marsh was when the five of us from our platoon met in Lexington, went to Rotary, and then visited the famous horse farms.

It may be interesting to note that, although our platoon had (estimated) 500 percent casualty turnover, all five of our top ranked NCO (non commissioned officers) survived—collecting four purple hearts between us, along with three Silver Star Medals, two Bronze Star Medals, one battlefield commission, and a Croix du Guerre Medal.

And we were all still very much alive to see each other again, 50 years later.

I am sure that reading this will be as difficult for you to read as it has been for me to write.

I can add that Marshall was my closest friend all the time we were in Service.

I was always fascinated by his sharp mind, quick wit, wonderful vocabulary—but most of all he was right there to be a friend.

You should be very proud of your family—nothing is more important!

Our Love,

Walt and Margo Freitag n