Undercover Brother

Afrocentric Web Hero Goes Hollywood

By Patrick Reed

"Two more added to the stable."

Thirty years on, the once-revolutionary currents of 1970s African-American popular culture are thoroughly ingrained within the modern hip-hop mainstream. Everywhere you look, signals to the Soul Train-age abound, from Nike's throwback to The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh ads featuring Bootsy Collins, to TV's Bernie Mac dressing up his teenage niece like Pam Grier for a party, to Shaquille O'Neal hawking super-sized sourdough burgers accompanied by Isaac Hayes's cymbals and wah-wah. The passage of time-the creeping effect of nostalgia-always has a tendency to chop up and simplify a cultural movement so that much of the original vibrancy is lost, and only a few familiar signposts remain. For instance, you don't hear very many shout-outs about Sweet Sweetback's "Baadasssss Song" or the Last Poets these days, but, as for Superfly and Shaft, well, those cats are everywhere.

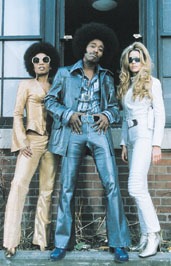

So, the brashness of 70s black culture in its post-Civil Rights ascendancy is now recalled as (and reduced to, by Hollywood and Madison Ave.) big Afros, shiny Cadillacs, Clyde Frazier fashion and string-laden soul music-basically harmless stuff these days, sure to get an acknowledging chuckle but little else. Coming a full 14 years after I'm Gonna Get You Sucka set the template for "old-school" nostalgia, the new Undercover Brother attempts to reinvigorate the formula, but in the end it's just another middling summer comedy.

Give the makers of Undercover Brother credit for their timing, at least, as this Eddie Griffin vehicle is dropping well before the new Austin Powers pic, which co-stars Destiny's Child siren Beyoncé Knowles as a Cleopatra Jones-ish blaxploitation heroine. The concept for Undercover Brother is straight from the burgeoning mega-scene of online entertainment; author, screenwriter, and frequent National Public Radio commentator John Ridley co-created the character of Undercover Brother for a web cartoon series that quickly became a word-of-e-mail hit.

In Ridley's series, the erosion of 70s-era Afrocentrism is revealed to be the result of "the Man's" mastery of multinational corporate influence...and, with the help of a few comrades in "The B.R.O.T.H.E.R.H.O.O.D.", the heroic Undercover Brother commits to infiltrate whitey's world in order to get America back on the good foot. Adapted to film, the new Undercover Brother plays, well, like a series of comic strips, with little cohesion and a visual feel and pace similar to that of the recent ADD-addled Charlie's Angels. While director Malcolm D. Lee's first feature, 1999's The Best Man, was no masterpiece, it did display a promising penchant for dialogue and character development, but here Spike's cousin is aiming for broad comedy and a funkadelic opening weekend. Predictably, the satire suffers.

Still, it's hard to expect much cutting-edge flavor to remain when a cultish Internet idea is blown up studio-size-this film is eager to entertain the widest possible audience, and what better way to do this than to employ the most pedestrian stereotypes at hand about white and black folks? What little plot thrust that exists in Undercover Brother concerns a mind-control drug obtained by "The Man." The serum is first used on a Colin Powell-esque presidential candidate (Billy Dee Williams), making him renounce his political ambitions and open a chain of, yep, fried-chicken restaurants. That's the tried-and-true level Undercover Brother stays on, for the most part: white guys without rhythm, sistas with too much attitude, smart black men who invariably use perfect diction, uptight whites that not-so-secretly wanna be black, and so on, not forgetting any and all matters relating to sex among and between the races.

Thus, the burden for making the film work falls on the cast. After a gig on UPN's Malcolm and Eddie, several supporting film roles, and time spent haranguing hoes on Dr. Dre's most recent CD, former choreographer and stand-up sensation Eddie Griffin gets to use both skills as Undercover Brother, and he brings to mind a more coarse and streetwise Sammy Davis Jr. in some of his mannerisms. However, the best jokes, the few laugh-out-loud ones, come from Dave Chappelle, who plays the super-paranoid Conspiracy Brother and seems to have merged some of his own stand-up routines into the dialogue. Conversely, the ladies (Wild Things' Denise Richards as White She-Devil and Men of Honor's Aunjanue Ellis as Sistah Girl ) aren't given much to do other than look lascivious, and recruiting eternally-annoying SNL dweeb Chris Kattan to play the primary evil honky is a clear signal that this movie is aiming for numbers first, not comedic nuance. Overall, Undercover Brother shovels out too much of the same old snippets of 70s black culture without capturing enough of its radical energy, and even a late, rousing cameo by "the hardest working man in show business" himself can't save this movie's super-bad soul.