|

Behind the Scenes with.... Bobby Ray.

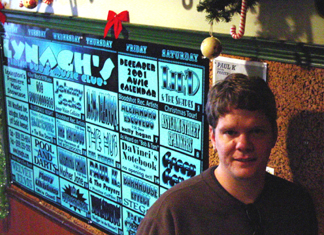

-Nick Hornby, High Fidelity "Alejandro who?" might've been a common question in Lexington back in the early 90s. This was before phrases like Americana and roots-rock became household parlance in the local lexicon. In March of 1995 (more or less), that all changed. That's when Bobby Ray took over the booking gig at Lynagh's Music Club, and assumed the mantle of Americana Director for WRFL. Next month, he'll wrap up his duties at Lynagh's and hit the road with the (Durango-based) Yonder Mountain String Band as their road manager. His first leg will include Colorado, Arizona, and the west coast - two vans and a trailer. As he tucks into a plate of cajun catfish, he admits one of the things he's anticipating is "a chance to eat two, maybe three times a day Because I'll be on the road with five other guys who expect to eat." But today, Colorado seems a long way off. Today, he seems content to reminisce. In May of 1995 came the first real test of Ray's mettle when he booked Robert Earl Keen (then relatively unknown), on a Tuesday night. Although Keen was already developing a cult following, to many locals he was still just Lyle Lovett's roommate from Texas A&M (perhaps best known as the co-writer of "This Ole Porch," if he was known at all). Not exactly a guaranteed sellout. Or as Ray puts it, "I was scared out of my gourd." But when the show came off without a hitch - and the crowd was of decent size, and serious enthusiasm, he concluded "hey, maybe I can get away with this." The music landscape hasn't been the same since. Ray is largely responsible for turning Lexington into a vibrant tour stop for acts like Keen, Alejandro Escovedo, Iris Dement, Kelly Willis, Kim Richey, Dale Watson, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Junior Brown, Monte Warden, the Derailers, Old 97's, Buddy and Julie Miller, Dave Alvin, Shaver (including the late Eddy Shaver), Victor Wooten (also known as Bela Fleck's bassist), Pete Anderson (along with most of the rest of Dwight Yoakam's band), the late Rick Danko, and Jay Farrar. And too many others to count. It's the rare midsize city that attracts artists of this caliber - and on such a regular basis - particularly in such a small venue. The artists frankly credit Ray with this development. As Alejandro Escovedo observed when he was in town a few weeks ago, he'd rather do two nights in Lexington, than add on another leg in a bigger city that isn't as responsive as the fan base he's cultivated in the bluegrass - a base he credits to Ray. Lexington is one of a handful of cities (Chicago and San Francisco among them) where he gets treated "like a rock star" when he comes to town. It isn't that Escovedo doesn't deserve the treatment - his last show was nothing short of transcendent - but there are far larger places on the map (for example, Minneapolis) where he doesn't sell out, and isn't half so well-known, much less appreciated. It wasn't always this much fun, much less easy. Ray had to develop a relationship with the artists and their representatives, and create an audience with little to no marketing or advertising budget, and then negotiate all the logistics, contracts, riders and finances that go with any show. As he points out, laughing, "it's not like ordering a pizza 'Yeah, I'd like a large Dave Alvin. Hold the anchovies.'" Still, he's turned Lexington into a stop that rivals markets twice our size in our ability to draw incredible performers, who consider the town an actual destination, and not just a play-through. That said, if there's been a criticism among the natives, it's been the slow and steady disappearance of local establishments that cultivate local talent - a tragedy that can hardly be laid at Ray's door. He notes that when he began booking, there was a lot of competition for the local music scenesters. Most obviously, there was the late-great Wrocklage. JDI also provided a stepping stone for bands looking for a place to play out - but who might've only been a few steps beyond Mom's garage. There was also Heresy and Area 51. All served a particular segment of the populace. Ray saw a niche that he could develop for Lynagh's - and Americana/alt-country/roots rock (post Uncle Tupelo) was hitting big. He saw the club as an extension of what he'd been doing in radio (at WRFL): "an opportunity to play music that I thought people should have an opportunity to hear." From radio to the club, his simple goal was "to fight for music that deserved an audience." It really wasn't anything any more grandiose than that. He certainly wasn't in it for fortune or glory - he put in nearly two years at the club before he even quit his day job. Still, he fought the initial perception that there was a conflict between his work at WRFL - which some accused him as using a platform to sell more tickets for the acts he booked. (In reality, he got paid the same either way. He could've stuck to a regular rotation of popular - if musically bankrupt - sellouts, and it wouldn't have changed his paycheck a penny in either direction). He said music lovers eventually seemed to realize that he was booking and playing the same acts for the same reason, "it was damn good music and it needed to be heard." He also fiercely maintained the integrity of his radio work, never incorporating the club's popular forthcoming acts into the playlist if they would jar the credibility of the shows' formats. It's been a challenging gig, but his eyes light up when he recalls the highlights. While it goes without saying that running a rowdy music club is no mean feat, it has its payoffs too. He recalls a night when Shaver (Billy Joe and Eddy) simply would not leave the stage. Eddy and Keith Christopher (their bass player, now with the Yayhoos) were tearing the place apart. The lights were up. The beer goggles were off. Still, no one would leave. Ray ended up doing double-duty as stage-security that night, guarding Eddy from a crowd that had spontaneously decided that it was acceptable to request autographs mid-performance - a crowd that included a memorably overweight redneck who kept drunkenly waving his Sharpie at the band, while simultaneously disrobing. As Ray reluctantly informed the band of the impending curfew, Billy Joe's response was, "Awwww Bobby Ray. We was just gonna play 'Tramp on Your Street.'" And so they did. And that was the last time many of us saw Eddy Shaver alive before his tragic overdose. That's just one moment, of course. But it's representative of many that have defined the club during Ray's tenure. He'll be missed. |

|

|

HOME | THIS ISSUE | ACE ARCHIVES |