Work Sucks- and then some

Rich get richer. Poor get poorer. Resentment builds.

By Alex De Grand

Thousands of people have raised hell in Seattle and Washington, D.C. over global trade, acting on their suspicion that working for a decent living is increasingly viewed by the government and business elite as a quaint notion of the Old Economy.

Even the University of Kentucky campus, which rarely rouses itself for anything beyond basketball and periodic tuition increases, has been the site of arrests over sweat shop protests.

American Labor has been out in front of this populist backlash to Clinton's New World Order. Yet, when it came time for the House of Representatives to vote on permanent normal trade relations with China, concerns raised by Labor risked freezer burn from lawmakers' cold reception.

It's a disconnect between the grassroots and the elected officials that isn't just restricted to national politics.

Events last week, many playing out within the city limits of Lexington, drove this home. While the state's leadership applauded the prospect of more "free trade," working people in Lexington and across the state let it be known they're tired of letting Business call all the shots.

The Big Blow Off

The dingy bar stashed in the bowels of the downtown Lexington Radisson seems a more likely staging area for one-night stands among hotel conventioneers than the place for Labor to make a last-ditch protest of runaway free trade.

But on June 14, as a flock of Kentucky government and business representatives cozy up to the visiting Chinese ambassador elsewhere in the city, the state AFL-CIO issued its warnings about China's record on human rights and labor practices from this corner of downtown.

To drive its point home, the AFL-CIO presented Wei Jingsheng, who spent 19 years in a Chinese prison for his political beliefs and has gone on to become a highly decorated activist for his people, claiming, among other distinctions, the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award in 1994.

But even if the AFL-CIO had managed to reunite the Beatles, nothing was likely to eclipse the ongoing free trade festivities.

The next day's front page of the Herald-Leader trumpeted bland statements from the Chinese ambassador that his country might eventually buy tobacco from Kentucky. The AFL-CIO earned a mention on page 13.

AFL-CIO President Bill Londrigan said there was a lot of discussion as to whether to bother with the press conference following the U.S. House of Representatives' vote to permanently normalize trade relations with China over the objections of organized labor.

"We decided it was important the voices of the Chinese people be heard," Londrigan said.

That Old Time Religion

The press conference could reinforce the impression that Labor is the Chicago Cubs of American politics: Lovable losers with a sympathetic cause that no one really takes too seriously.

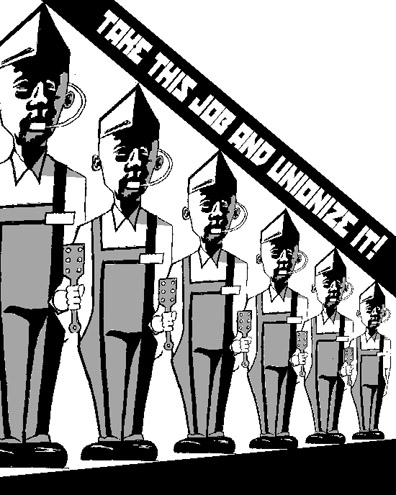

Yet if that morning's press conference portrayed Labor as prophets blown off by a town falling in love with a golden calf, a meeting of the Lexington sanitation workers later that day at the community center off Georgetown Road was a veritable tent revival of Labor's core principles.

The meeting was attended by representatives of several activist groups, including the Central Kentucky Council for Peace and Justice and the Democracy Resource Center. The meeting also drew candidates for city council, Robert Moreland and Dale Edinger, and Councilman Al Mitchell.

The meeting was a chance for sanitation workers to explain to the community how challenging their jobs are. It was also billed beforehand as an opportunity for the workers to discuss the possibility of unionization.

The sanitation workers start at $7.50 an hour, a wage even the city's own housing study finds too small to adequately cover the expenses of a typical one-bedroom rental unit.

And, as the workers recounted with appalling detail, the work is often nasty, dangerous, and physically demanding.

"When I first started, we were called 'garbage men,'" said worker Robert Simmons. "That title has changed... But people still think 'They can't be too intelligent. They can't be worth too much.'

"In medieval times and in other countries, they have a caste system... It's not supposed to be this way [in America]," he said.

Simmons and his fellow workers told the crowd of about 50 people about the awful anticipation of opening a Herbie. Who knows what'll be inside. Dead animals? Emptied bed pans? Syringes with hepatitis? Virulent chemicals?

Simmons held up a bottle of bloody cotton swabs and hypodermic needles before the crowded room.

"What are we supposed to do with this?" Simmons asked rhetorically. "Go on and get it."

"We've got to dump it into the truck," Simmons continued. "If it falls out [of the Herbie], we've got to pick it up... People are supposed to bag it, but they don't."

And while dealing with the garbage, Simmons said a sanitation worker has always got to look out for motorists.

"It's not 'if' but 'when' someone [is] going to get hit by a car," Simmons said. "[Motorists] may slow down for an animal, but they won't act like we're even there."

Hamilton Cole, another sanitation worker, held up his hand to show where he lost part of a finger while on the job. He thanked his co-worker for quickly getting him to a hospital because he could have bled to death.

Cole said the accident occurred during his third week on the job. He said he was terrified he would be fired.

"When my supervisor came, I was saying, 'I'm sorry. I'm sorry,'" Cole said.

Cole called on his audience to unite behind the sanitation workers.

"Everybody needs to pull together," Cole said. "It's not just about the money. It's about our lives. We can't make money when we're dead."

At the meeting, attorney Theodore Berry urged the workers to be united.

In the early 1970s, Berry, as a UK law student, worked to alleviate the working conditions found in the sanitation department. Berry said many problems persist today even after nearly 30 years.

"They don't have adequate representation to fight for their rights," Berry said. "People come in individually (to complain to a supervisor). They need a spokesperson who can present the issues and know the resources available."

Sanitation worker David Sams said no decision on unionizing was made following the meeting. However, Sams said, if the sanitation workers decide to unionize, he would like them to organize with other city employees like the firefighters.

The mayor's budget proposes increasing the sanitation workers' starting wage to $8.26 an hour, according to a city spokeswoman. Sams derided the increase as too small to make much of a difference and he suspects token raises are a strategic move to break a drive toward organizing workers.

But Sams said he doesn't think the ploy will work. According to Sams, an extra 76 cents an hour won't pay that many more bills when you've got children to raise.

We Got A Big Ol' Convoy

Two days after the press conference at the Radisson, the Kentucky AFL-CIO took about 25 activists from Louisville to Pikeville to highlight the problems of working people trying to organize a union.

Like some bizarre A-Team episode written by Eugene Debs and George Meany, the charter bus pulled up to be greeted by frustrated workers. Activists filed off the bus and were handed picket signs from a stockpile stored in the vehicle's luggage compartment.

Armed with banners and chants, the group would typically gather from the sidewalk or roadside of the offending institution and unleash a barrage of speeches and songs.

Many workers were openly relieved to have the out-of-town support.

During the stop in Jackson where employees of the Kentucky River Medical Center have fought for two years to secure a union contract, there was a palpably festive feeling.

Like some impromptu Oprah-style outpouring, jubilant employees took the microphone and let loose with testimonials about how lousy it is to work for the hospital's management.

As the hospital managers endured the tongue lashing, tired-looking security guards slouched up against cars in the parking lot. Security wasn't present at most of the tour stops.

At many of the events, the crowd was joined by politicians.

A Louisville alderman joined protesters outside the American Printing House for the Blind where management refuses to bargain with its workers who want health care and sick leave benefits. The Pike County judge-executive greeted a raucous crowd rallying against the management of Pikeville Methodist Hospital which has resisted a union contract.

When the bus stopped in Lexington, state Rep. Kathy Stein was there to throw her support behind the tour and the workers looking for a new contract with GTE.

After speaking to the crowd, Stein said the problem facing Labor in Kentucky is organization.

"The Labor movement is bombarded by groups lobbying against progress for workers' futures," said Stein. These groups are framing their arguments better and outmaneuvering the unions, she added.

Stein noted in the last legislative session, a bill to grant public employees the right to collective bargaining didn't even get off the ground despite the fact that the bill had the governor's backing.

Echoing what many AFL-CIO officials are saying themselves, Stein explained it's all about numbers.

According to the Labor Cabinet, Kentucky has about 250,000 workers covered by union agreements. Stein said Labor needs to augment that figure by building alliances with churches, Hispanic groups and activist organizations.

The bus tour offered evidence such coalitions can be built.

Father Joe Graffis of St. Augustine Church in Louisville was one of many clergy members to come out to support the AFL-CIO tour.

"There is a moral issue here," Graffis said as he stood listening to the speeches given outside the American Printing House for the Blind. "These [workers] give their time [for] a valuable contribution to the community. There needs to be some justice with that... At least sit down and negotiate."

Graffis said the church can provide leadership with raising the conscious of each side and bring them to together to negotiate. He added churches can take the lead with educating the public on these issues.

The Court of Public Opinion

And what about the public?

According to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 13.9 percent of the nation's wage and salary workers - or 16.5 million people - were in unions in 1999.

That suggests an average American's knowledge of unions is unlikely to come firsthand or from a friend or neighbor who belongs to a union. There are a lot of misconceptions about unions, including whether they should even continue.

"The cliché is unions aren't necessary anymore," said Ted McCormick of the Center for Labor Education and Research at the University of Kentucky (CLEAR).

"But that's disproved every day by what's going on nationally and around the world," McCormick said.

McCormick was heartened by the UK student protests over sweat shops, showing there is interest in the issues unions have been raising for a long time. He said the unions need to continue reaching out to tell people about what's going on.

And there's reason to think people will be receptive to messages beyond sweat shops, given some reactions when the AFL-CIO bus stopped at a McDonald's in Louisville.

The activists were wandering around the McDonald's parking lot, distributing handbills denouncing the wages and working conditions found at the Cagle-Keystone chicken plant in Albany. Cagle-Keystone supplies chicken products to McDonald's.

As activists went about their business, a guy buying coffee at the Thornton's gas station next door asked the clerk what's causing all the commotion.

"It's the poultry union," the cashier answered.

"Are the chickens on strike?" the man smirked, impressing himself with his wit.

The cashier stared at the man and then explained the protest was aimed at the poverty-wages and improving working conditions of a chicken plant.

CLEAR Director Paul Jarley said of the cashier's response that people tend to be sympathetic when they know that much about the issue.

Who knows whether the man became anymore enlightened from the exchange. But it seemed the poultry workers have a friend at Thornton's.

A Challenging Future

Unions have their work cut out for them.

"I'm not going to sugar coat this," Paul Jarley told the activists on the bus when asked about Labor's future. "In the short term, the prospects are difficult at best."

Jarley said just stopping the Labor movement's bleeding would be a success.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports union membership stood at 20.1 percent of the American workforce in 1983, the first year it kept data comparable to contemporary statistics.

By the middle of the 1990s, the union share of the nation's workforce was at 14.9 percent and the bureau reported that rate dropped to 13.9 percent by the last year of the decade.

Jarley said one of the problems confounding organization efforts is the economy's shift from manufacturing to service sector jobs.

A factory had thousands of employees so organizing one of them was a big boost, Jarley said. But in the new economy, a place of employment may not have any more than 50 people, he said.

Organizing takes longer and the rewards are substantially smaller. Meanwhile, employers are putting up more resistance to unionization and the costs associated with organizing a big factory are about the same as those with organizing a small information-age business, he said.

Jarley suggested unions could begin organizing by trade or occupation like the 19th century guilds.

Potentially helpful in the effort to increase unionization is the fact that unions still boast a wage advantage over their non-union counterparts. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported union members had median weekly earnings of $615, compared to $462 for non-union members in the mid-1990s. That advantage remained by the end of the decade - $672 a week for union members and $516 for non-union members.

AFL-CIO President Bill Londrigan said it is up to his organization to make people aware of their rights to organize. He argued the current political climate has been so unfriendly to unions that people don't even know what their rights are under federal law.

Londrigan blamed a hostile political climate for contributing to people's ignorance of their rights as workers.

Ironically, changing that political environment depends on gaining new members.

"You're only as big as you are and the problem in Kentucky is that labor isn't that big," said Don Meade, a Louisville labor attorney. "When you break it down by occupation, we're really not that big."