[three_fifth]

Must See TV

Kentucky-grown film team find small screen success with NBC’s Siberia

BY KAKIE URCH

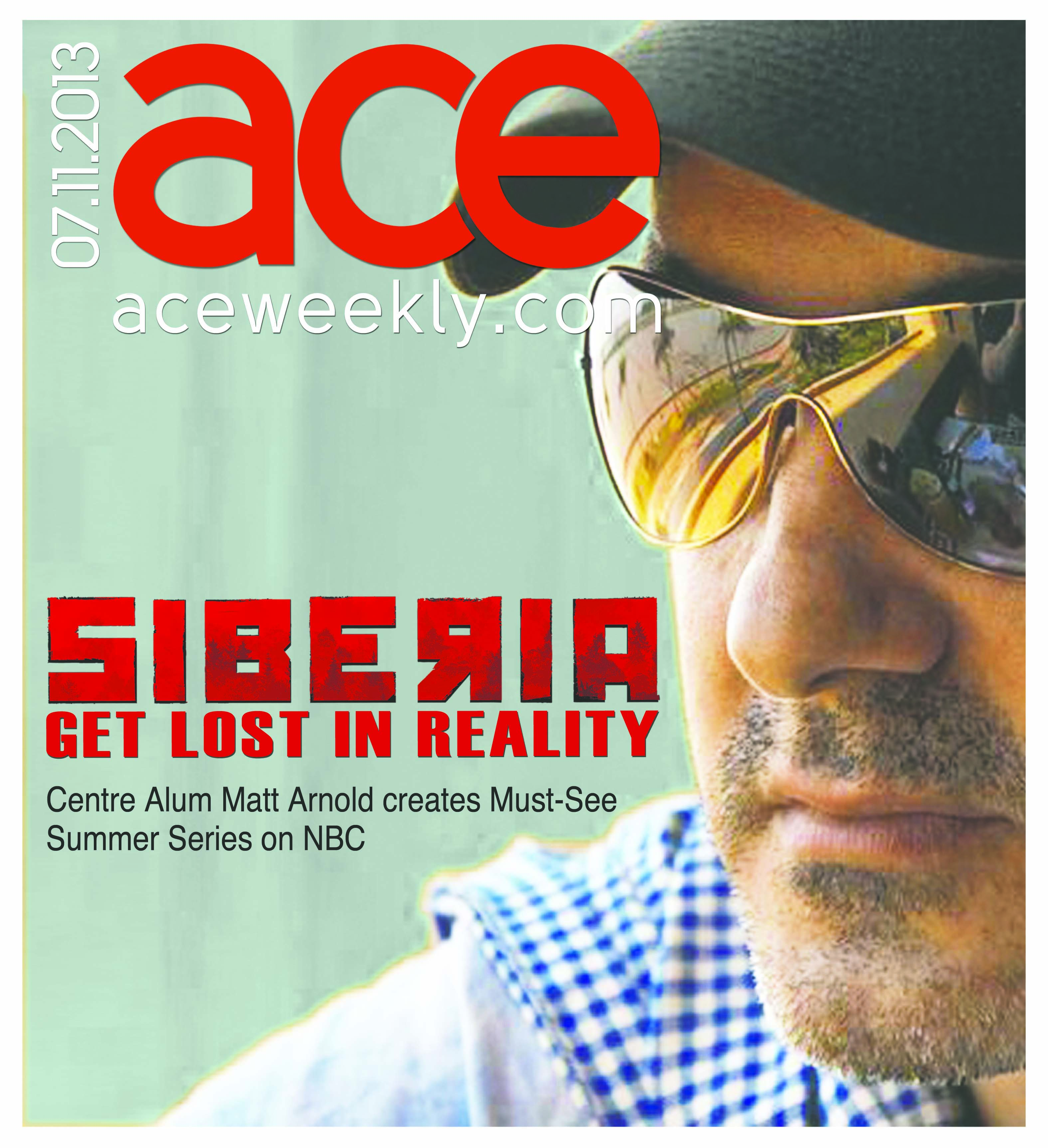

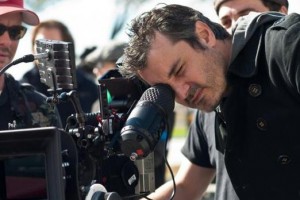

Centre College alum Matt Arnold is the creative and practical force behind the concept, production and direction of the 13 episodes shot in Winnipeg Manitoba Canada (doubling for Siberia). After a chance reunion at the Cannes Film Festival, he cast his fraternity brother, Centre and Sayre grad, actor George Dickson: as a salmon-blazer-and-palm-tree-print-polo-wearing Kentuckian. “I have always been interested in film ever since I was a kid and my father gave our family a video camera. I made dozens of movies in high school and even made one at Centre before attending USC, “ Arnold said in an Ace interview earlier this week.

The character, “George,” is just one of a group of 16 people dropped into the Siberian wilderness as part of a reality show.What they hadn’t signed up for and aren’t aware of is that that the area near Lake Baikal where they have been dropped is the site of one of science’s (and science fiction’s) biggest mysteries: The Tunguska Event. Whether it was a meteorite, a natural atomic bomb or aliens

that generated the incredible impact and burning force in the Siberian woods in 1908, it apparently is still out there.

If making it through winter in the Siberian forest for a prize of $500,000 weren’t difficult enough, just make that a horrific, horrible, haunted, maybe radioactive forest. The twist thrown at the contestants is that they must make it through with the clothes on their back. Shot by a camera crew that had more than 100 actual episodes of Survivor under its belt, the camera work and production values work to evoke the reality show aesthetic within a horror concept. The characters created by Arnold hit the reality show tropes and archetypes – including the just-off-the-polo-pony Kentucky anti-stereotype.

Once you meet the group, you want to know just how these individuals will react to the challenge. Dropped in Siberia in a sleeveless bright yellow blouse and a miniskirt, for example, what will you kill and sew up to stay warm in the rebuilt “abandoned settlement of 24 people?”

Two episodes had aired at press, with a few scary turns taken in the “game.” One girl on a mushroom trip assures her castmates, “You’re all gonna die.” Viewer interest has been piqued by the unique format – ‘reality’ show within a scripted series. Arnold is the creator, writer, director and producer for Siberia, and is also receiving praise for his recent independent feature film Shadow People. The reviews of Siberia from some of the critics that matter have been positive, hopeful and full of praise for Arnold’s inventiveness. The USC Film School grad has been praised by reviewers from the Los Angeles Times and New York Daily News and lauded as a deconstructionist of genre by The New Republic.

Like most buddy stories about Kentuckians, this one begins at Cannes. That’s where the two men who knew each other in college reconnected. Dickson, a bond analyst turned actor, was at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival as the producer of a short (Fiasco) that made it to the festival, and Arnold was there with one of his projects. Dickson said, “A year passes and I’m in Kentucky and he contacts me to start interviewing for his show. Three rounds later, I was given the part.” The two worked together to create the character which is an indigenous but less well circulated species of Kentuckian than “the stereotypical view of Kentucky being very country.” Arnold said to Dickson “You and I both know that Kentuckian that people don’t know.” So, Dickson said, “I would go to different thrift shops and work on my costume. I had a great time with the costume.”

“I almost look at acting and film as a war of attrition and if you keep yourself in the game long enough, you’re going to have some success. I am grateful for a good friend sending the elevator back down, to quote Jack Lemmon.”

Dickson praised Arnold’s directorial skill on the August/September 2012 shoot and his recent good fortune in Hollywood. “Matt was just signed with ICM, kind of like being the fifth pick in the NBA draft.” (ICM is the group that reps film directors including Woody Allen and Sofia Coppola and tv show packages including Modern Family, Grey’s Anatomy, and Breaking Bad.) In describing Arnold’s style on set, Dickson said: “I would use terms like ‘driven,’ ‘fearless,’ ‘extremely inventive.’ He sticks to his guns and really takes care of his actors.” Arnold says, “Agents there approached me after news of Siberia selling to NBC broke.”

Arnold has been working steadily toward his recent success – ever since he was a production assistant on Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown (1997). “Working for Tarantino was a dream come true. Quentin was really open to giving advice and at the end of every week the crew would go to the bar and Quentin would ‘hold court’ and we could just pepper him with questions. It was film school before film school,” said Arnold, who got his USC degree in 2002. While working in Tarantino’s office, Arnold saw Good Will Hunting before it became a film and, with his background in physics from Centre College, wrote the math equations that were used in that Oscar-winning film.

Arnold has a TV rep and a film rep because he’s shown success in both. His interest in “found footage” work and scary narratives are shown in the current feature film Shadow People.

Arnold said: Shadow People is a psychological horror story about a true phenomenon. People all over the world for centuries have reported waking up in their beds, but their body is still asleep (known as sleep paralysis) but in an estimated 20 percent of cases they see a dark shadowy figure in the room with them. What these entities want and how they spread is the subject of the film.”

“We used dramatic scenes incorporated with real footage of interviews and eyewitness accounts. It’s been reviewed extremely well in the press and has been selling excellently all over the country,” he said. So, Siberia, Arnold’s next horror hybrid, seems only natural. As for the Tunguska Event, the disclosure of that paranormal element to the cast came as it did in the “reality show,” from the “host” of the show. So, the confusion and fear experienced by the cast is based on a real unknown. The Tunguska Event is one of the most referenced scientific phenomenon in pop culture, and is the basis for several works of fiction. “Explanations” range from a meteor to aliens to an accident at a Nikola Tesla experimental station.

Dickson said he thinks fans of the paranormal and people who like being scared and watching a little drama will like Siberia. Arnold said that his advice to a young Kentuckian with film and television writing or directing aspirations would be, “Stay with it. if you really want to do this you have to treat it as a career and give it everything.”

There are photos on Arnold’s facebook page of him working with Harrison Ford, but the meaningful teachable experience he recalls is less glamorous. “I think working with Wilford Brimley on my student film ‘Resurrection Mary,’ which we shot in Kentucky was a major learning experience. He taught me a lot about working with actors and how to inspire and lead,” Arnold said.

“Wilford is such an amazing man that he actually gave me back the salary I paid in exchange for a favor. He said, (and I’m paraphrasing of course) ‘you’ll need the money for post-production, so keep it, but you’re going to do me a favor. Some day some kid is going to come to you and ask him to help you on a project and you’re not going to want to do it, but you’re going to do it because I did this for you. And that’s how people ought to work in this business.’” “I thought that was remarkable,” said writer, director, producer Matthew Arnold, Centre College, ’96.

Siberia airs on NBC Mondays at 10 p.m. Follow the show on Twitter @NBCSiberia.

Kakie Urch is an assistant professor of multimedia in the University of Kentucky School of Journalism and Telecommunications. She has been to Siberia. The real one.

[/three_fifth]

[two_fifth_last]THIS is Siberia… for Real?

BY STACEY PEEBLES

If you watched the premiere episode of NBC’s new show Siberia, you could be forgiven for thinking that you’ve seen this kind of thing before. The stage is set: a group of blindfolded men and women; a wilderness clearing; a tan, serious host; and a challenge, with a lot of

It’s a familiar story by now, and the show’s use of jerky hand-held cameras, dramatic editing, and a subtle soundtrack to underscore moments of emotional intensity are familiar as well. (They ought to be—the producer Doug McAllie worked on over 200 episodes of the reality heavyweight Survivor.)

Soon, though, doubt creeps in, both for the contestants and for us, the audience. As the group settles in to its camp deep in the Siberian wilderness, they hear strange sounds, find a mutated frog, and by the episode’s end, one of them has been killed. A cameraman is badly injured, too, and various crew break the frame to deal with the crisis. The host, Jonathan Buckley (former host of Lifetime’s 2012 reality show Love for Sail), returns looking shaken; he announces “a very serious accident…and unfortunately, it’s fatal.” The show ends with footage of the dead competitor, taken by the cameraman, as he ambles along looking for food, and then suddenly screams and runs. The camera falls and lies on its side, then cuts to black.

That last shot is a cinephile’s clue, a nod to the last shot of The Blair Witch Project (1999). While Siberia takes its format and some of its tone from shows like Survivor and Lost—the influences most often mentioned in articles about it—it owes more to “the little horror movie that could” from almost fifteen years ago. Under the guise of documentary, that film presented itself as the found footage of a trio of ghost hunters who came to a supernatural and presumably grisly end. Bolstered by a website with authentic-looking police reports and interviews, the filmmakers managed to convince a good portion of their audience that the events were real, at least for a while, instead of the subject of a fictional film that was very cleverly planned, shot, and cast with actors demonstrating strong improvisational skills.

Siberia, it turns out, is doing the same thing, and if we’re not quite as gullible as we were in 1999 (if we ever were), the premise and the skill with which the conceit is executed are a pleasure. The host has his reality-show bona fides, the contestants are listed in the title sequence by just their first names (the same names as the actors’ own), and, sadly, real fatalities in the world of reality television are not unprecedented. (Melissa Maerz, writing for Entertainment Weekly, mentions Russell Armstrong’s suicide and The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, as well as a number of deaths of people associated with Celebrity Rehab.)

The show’s creator and director, Centre College alum Matthew Arnold, has said that this potential for real disaster was the inspiration for the show. “I remember watching Survivor and they were putting them in some exotic location—I was thinking, gosh, I wonder would they ever be so stupid enough to put one of these reality shows in a dangerous location where, you know, some rebel faction is warring or something? And what if that rebel faction or pirates, Somalian pirates or something, came across this reality show, and what would happen? And what if the cameras were still rolling?”

Modern media has a long history of playing with that boundary between fiction and reality, from Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast to the digital verité elements of contemporary horror movies. When Robert Flaherty directed the first film documentary Nanook of the North in 1922—so long ago that “documentary” wasn’t even a category yet—he thought nothing of staging, changing, or just making up elements of his “authentic” look at an Inuit family. (Nanook’s wife in the film, for instance, wasn’t really his wife, and his name wasn’t really Nanook, either.) More recently, we might complain about the way that reality shows tease out conflict and drama with contrived situations and drastic editing choices. But we keep watching, either because we’re happy, in whatever guise, to give in to the suspension of disbelief, or because a good story is just a good story.

So far, the verdict is that Siberia’s particular mix of the real and the created does make for a good story, and the reviews have been positive—with one notable exception. The Siberians themselves aren’t too happy. In the context of this reality-show genre that traffics so much in stereotypes, The Siberian Times objected to their own region’s presentation as an American idea of Siberia, “mixed with a cocktail of Hollywood horrors and then frozen in a Cold War time warp.” The makers of this “TV fake” aren’t even showing the real Siberia, they say.

The show, it turns out, is shot in Canada.

Stacey Peebles is Director of Film Studies at Centre College and author of the book Welcome to the Suck: Narrating the American Soldier’s Experience in Iraq (Cornell UP, 2011).

[/two_fifth_last]