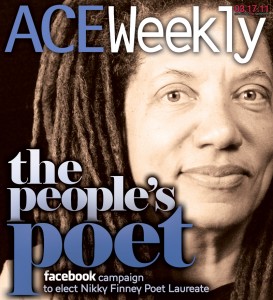

I remember my first time seeing Nikky Finney read her poems. I was nineteen years old and had just started to put together pieces of poems and little did I know that the Affrilachian Poets were about to change the course of my writing forever. I was standing in the back of a packed house in the Carnegie Center and watching these writers take the house by storm like rock stars. And then. A tall, latte-skinned woman with olivine eyes and waist-length brown dreadlocks stepped up to the lectern and it seemed as though the entire audience inhaled together. None of us let that breath go until her last word. When I could collect my thoughts, I distinctly remember thinking, “Someday, I want to do that.”

Some months later I was in Joseph-Beth and wandering around the rows when I saw her again. It sort of felt like casually running into Glinda the Good from The Wiz, “You’re Nikky Finney,” I blurted. And she smiled. Today, if you go to Jospeh-Beth, chances are, you’ll see Nikky too, but this time smiling from the cover of the Spring issue of Poets & Writers, the writers’ equivalent to a sports fan seeing a beloved MVP on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

University of Kentucky Professor of Creative Writing, Nikky Finney, author of On Wings Made of Gauze, Rice, and The World Is Round, finds herself taken with the no holds barred launch of her new collection, “Anything that has happened for me and a book was because I put the book on my back. I put it in my trunk. I got in a car or walked or got on a plane and took it wherever I was going…I just never had this kind of beginning. You do the work with the book. You work for five or six years and then it comes back and you say okay now what do you do, which direction do you go? That’s totally different with this book.”

Many elements have changed since Nikky’s first collection. Social media and web forums have made it easier to connect faces and events and politics and literature, “It’s not social media anymore. It’s political media. It’s progressive media…so this book thing is happening in the atmosphere of that.”

And on the heels of her striking, heady new collection, Head Off & Split, that is already enjoying much success, there is a Facebook campaign to nominate her for the 49th U.S. Poet Laureate, “I don’t know who’s behind this—I kind of don’t want to know—I don’t know what to say. I’m really kind of speechless about it. It matters to me. It matters to me in a very deep way because all of I’ve ever wanted to be is a poet. The other stuff that I do is important and feeds into it, but all I’ve ever wanted to do is be a poet. Thinking that somebody would nominate me for the country’s poetry position is just, it’s pretty—I don’t know.”

But for people who have followed her work, a groundswell initiative to formally name Nikky as The People’s Poet comes as little surprise. Writers and literary enthusiasts in and out of the classroom setting have felt the direct impact of her words for decades. Nikky recalls a reading with the Affrilachian Poets in Lynch, Kentucky, “This black woman is in the audience and she’s sitting there and she has a shoebox. And she’s listening to us and we’re doing our thing, and she comes up to us afterward and she opens her shoebox and it’s just poems. She’s like, ‘I’ve been waiting on you all for my whole life.’ She’s living in a place called Lynch, Kentucky. She’s got no community of black artists and we’re just passing through, and yet that moment was such a moment of verification for her.”

This leads to a memory of another pivotal instance while reading to a group of incarcerated women, “I’m looking out. They all have on cotton dresses. They’re my aunts. They’re my mother. The faces of women who’ve taught me English. Taught me how to cook. Made chocolate cookies. I cannot speak. Eight-hundred. One stands up, and she’s not supposed to…She goes, ‘Thank you so much for not forgetting about us.’ And I go, ‘You’re welcome.’ And I read my poems. And the bell rings, because you know they’re on a really strict clock. And I had fifty minutes to read and I think I read like fifty-one and the bell rang, and they get up and they don’t want to leave…it was the most amazing moment.”

What propels Nikky as a writer is often, quite literally, forward motion. Her father used to drive her an hour or two or three down the road, “And he got us out of our little tiny, tiny Southern town and he’d say, ‘Look over there. What’s happening over there?’ What he taught me is you gotta move. Movement. You gotta keep moving.”

To this day, Nikky still uses the forward motion of a car to inform her work. If she’s hit a stopping point, she sets her timer for an hour and drives in one direction with no stoplights. When the timer goes off, she turns around and drives home for another hour, “By the time I get back, I swear, it has never failed me, I have figured something out that I could not figure out just sitting there. So, for me, I am a child of being thrown in the car and being told, come on, let’s go. If you’ve never experienced that, you can’t explain it to anybody. I’m just like, no music, just holding onto the wheel, and I’m consciously thinking about why I got in the car, so I’m like that’s a lousy phrase, that word is not—by the time I get back, I’m closer to it.”

But in order to “wrestle poems to the ground,” Nikky also has found she must have a tether to a place she calls sacred, “Every time I move, it shakes me to my core…I can catch words and ideas almost any place…but to really go down and deep into the water, that is a space that is sacred that I know has some burn marks and some tear marks and some sweat and that’s a space that I can’t move to another place and immediately have…there’s some kind of womb space thing that happens for me that I protect passionately. So, actually my being here in Kentucky…that helps me understand that this will manifest itself in my writing in a deeper way.”

Nikky’s last Lexington reading for the book tour of Head Off & Split:

Holler Poets Series

Wednesday, March 30

8 PM

Free

Al’s Bar

Bianca Spriggs is the author of How Swallowtails Become Dragons. Order at http://www.accents-publishing.com or http://www.biancaspriggs.com.

HEAD OFF & SPLIT: REVIEW

Nikky Finney’s Head Off & Split , revolves around incremental discoveries. These poems are about microcosmic encounters with macro effects stretching from private to political spheres often with blurred borders. Winding through this collection there streams a pervasive current of identity, an acknowledgment of some facet of personality, upbringing, or spirit, that results in an event or realization about the larger picture.

The collection took root several years ago while on a familiar errand. Finney recognized in the question she’d been posited a hundred times by the man in the fish market, ‘Head off and split?’ another question at hand, “I started thinking how in the world, this is the problem. That if we didn’t hand over the dirty work…if we all took responsibility of what we know and what we don’t know—wow. Look how that would move forward the conversation…We’re not leaving it to one politicious soul to stand up in front and say, I’ll lead you. We’ll lead ourselves.”

In “Red Velvet,” a poem about Rosa Parks, Finney reminds us of Parks’ trade which informed her work within the Civil Rights Movement, “We never talk about her acuity as a seamstress…Rosa Parks was an operative. She was sent by the NAACP into small towns in the South to interview black women who’d been sexually assaulted or violated in some physical or sexual way to see if they were capable of standing trial…we talk about Rosa Parks as though she was on the bus just being tired. She was not tired. She was not, and yet that is the mindset we give students.”

From the introduction of a girl-turned-woman on a familiar errand, to a re-membering of Bush’s final State of the Union Address, a suite of poems about Condoleezza Rice, unflinching poems about the body, about love and love-making, the miracle that is maternal love, and the poet’s encounter at her brother’s wedding watching members of her family line up to dance with Strom Thurmond, the range of these poems is comprehensive. They are full-bodied and fully-loaded, at once intimate as much as they are cinematic in scale.

In this collection, Finney reveals herself to be a master spellbinder for all walks of audiences to engage, “If they read my work, it will come through how much I love being a black woman in this world. But they don’t need that as a ticket to get in. They just need to come. They just need to be open to listening and having a conversation and the stories that I want to tell. If they’re open to that, that’s all I ask.”

HOW LEXINGTON INHERITED NIKKY FINNEY

In the late 1980s, Percival Everett, who at the time was an Associate Professor at the University of Kentucky, happened to be in Charleston, South Carolina on a panel about black writers in the South. Also on the panel was Nikky Finney in her late twenties, who had been living in Oakland with one book of poems, On Wings Made of Gauze, under her belt.

Not long after returning to California, Nikky was contacted by UK about an open Visiting Writer position for which Percival had nominated her. It seemed like a bittersweet opportunity albeit in a setting she might not have initially chosen, “I was working at Kinko’s as a manager running the midnight to morning shift…But I had read so many interviews with artists and writers talking about the influence of the academy in a negative way so I was trying to really stay away from that imprint.”

A writer with an innate sense of wanderlust, Nikky wanted to see the world, “That was my desire. I was twenty-three or twenty-four when my first book came out. And then I moved out to California…I knew that traveling was—all the writers tell you you gotta move around, you gotta see the world, you gotta leave home. And I had always done that. I had left home at seventeen…I was the one who always had to sort of go and see and write about it and come back and tell everybody else about it.”

Nikky decided to accept UK’s invitation, sight unseen, to come teach and write for a year, “I thought, where in the world is Kentucky? But, right before they called, I had this idea for a second book of poems and the job was killing me…Long story short, I said, I will teach two classes. Let’s just go try it. I could not believe how much writing I got done.”

For those who love her collection, Rice, they might be surprised to know in that first year, 1989-1990, Nikky finished the entire first draft of those poems, “This is the writing life. You have to make time. You have to have time to write. So there I was with this draft. And I went back to California. I went back to Kinko’s. The chair calls me to say, ‘Your student evaluations are amazing. Would you come back again?’”

The lure to return to Kentucky was increased by her position becoming tenure-track, “I was just about to turn thirty. Had never had health care. No health insurance. No dental insurance. None of that. I talked to my family and they were like, ‘Go. You need to do this right now.’ I was contemplating having a child and healthcare was critical at the time in that notion, so I was like, you know what? Let’s just go. It may not work out. It may work out. So I went.”

And Nikky found herself in love with teaching. She was granted tenure and has appreciated the support of her department when she steps away for a year or two to stay active as a writer, sometimes taking her to somewhere as close as Berea or as far away as Smith, “I don’t know that I would have stayed here had they been more rigid in how I had to do this. Their support has been critical to my remaining here for almost twenty years.”

[amazon asin=0810152169&template=iframe image]