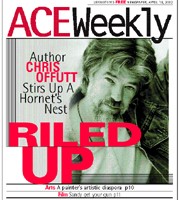

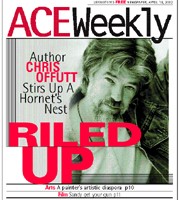

Ace April 18, 2002 coverstory

Fightin Words

Chris Offutt’s Latest Work, No Heroes, Stirs the Home Fires in Kentucky

No matter how you leave the hills—army, prison, marriage, job, college—when you move back after 20 years the whole county is watching carefully. They want to see the changes the outside world put on you…Put their mind at ease…Make sure and drive a rusty pickup that runs like a sewing machine. Hang dice from the mirror and a gun rack in the back window. A rifle isn’t necessary, but something needs to be there: a pool cue, a carpenter’s level, an ax handle… Tell them it’s a big world out there…Don’t talk about the beautiful people in stylish clothes. Never mention museums, opera, theater, or ethnic restaurants…Be prepared at all times to say it’s better here. You spent 20 years trying to leave this land and 20 more trying to get back.

—Chris Offutt, New York Times Magazine, 1998

If you believe last weekend’s controversy chronicled in the daily paper surrounding the new book, No Heroes (one article and a review the next day, if that can amount to controversy), author Chris Offutt has clearly gotten above his raisin’.

Because, if you believe the press, you might be tempted to think he is “condescending.”

“Arrogant” even.

Throw in maybe contemptuous and conceited and you’re catching on to the spirit of the coverage he’s received in the last week.

And if you believed it, you’d be wrong.

It might even cause you to dismiss Offutt and his work, when he is one of the finest writers Kentucky has sent into the world for his generation.

Yes. Offutt has been known to be ornery on one or two occasions (he confesses freely, in print and in person, that most people from his childhood assumed he was headed for prison or an early grave).

He has been known to get angry (with the exploitation of Eastern Kentucky’s resources, and its well-documented “brain drain” where the best and brightest leave because they have to, to find work).

And he’s been known to be impatient, with Appalachia’s subsequent embrace of Wal-Mart, the paving over of his hometown, and the rest of the homogenization of the South, especially the Mountain South (true of Eastern Kentucky, but by no means exclusive to it). He was also profiled in the New York Times Magazine on the release of the new book.

But in the Herald-Leader‘s weekend newspaper coverage, you might have missed all the complexities surrounding the hope and confidence and exasperation he feels for home because they’re conveniently dismissed and packaged with simplistic labels like “arrogant.”

For example, “that wretched cover photo with the apparently stuffed possum” is cited as one of Offutt’s many transgressions in the book-the review of which wore a savage subhead that called it a “268-page insult to Eastern Kentucky.”

(The maligned marsupial will be known to all Offutt fans as Joe Tiller’s possum, from his critically acclaimed novel, The Good Brother. In the spirit of full disclosure, the photo was also the cover of the November 16, 2000 edition of Ace, which

contained an essay by Offutt, “Getting it Straight,” which later served as a prologue to a new edition of Kentucky Straight.)

Last weekend’s review charges that “the trouble with No Heroes is that the author’s biggest hero is himself.”

Certainly, any understanding of his latest book would be informed by a thorough acquaintance with his earlier work (Kentucky Straight, The Good Brother, Same River Twice, and Out of the Woods), but it’s difficult to imagine that even a complete newcomer to the author could draw a conclusion such as this. His work is always, always informed by an underlying sense of humility – humility at the task before him, and reservations as to whether or not he’s equal to it.

He’s accused of factual errors, but the substance of his observations that seem to have incited the biggest fuss – one being that it is difficult to find metropolitan access to artistic and cultural and culinary diversity in a small mountain town – are as accurate as they are obvious.

It’s not necessarily an insult, and it is a fact that’s glaringly apparent to anyone who’s ever lived in a rural area.

More importantly, Offutt also takes ample time to praise many of the Thoreauvian compensations that accompany a rural life, while acknowledging that there are (of course) trade-offs.

Offutt isn’t the first to leave the hills in search of a better job or better schools for his kids, and he definitely isn’t the first to write about that in an honest fashion.

Yes, there are comments (quoted out of context) that might lend themselves to misinterpretation, but even a cursory overview of the book makes it clear that the author is writing about his roots and his homecoming with affection, conflicting emotions, and, when warranted: criticism.

How insecure would any of us have to be about our heritage to feel threatened by this in some way?

Although he frequently cites James Still as ‘the greatest Appalachian writer,’ and glows with admiration when he talks and writes about River of Earth, Offutt himself is not that type of Appalachian writer.

And although he lauds the work of Gurney Norman (Kinfolks: The Wilgus Stories) and Lee Smith (particularly Black Mountain Breakdown), his work bears very little resemblance to theirs.

He is not cast in their mold. Nor should anyone ask him to be.

He’s also not a late-model Wendell Berry agrarian. He’s not the Barbara Kingsolver bio-environmentalist.

And he’s most definitely not the cultural rapist and opportunist you might be tempted to believe he is, if you believe everything you read.

He’s blunt. He’s authentic. And he is most assuredly, the real deal.

Where you come from is gone, where you thought you were going to never was there, and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it.

-Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood

The love Offutt can feel for home is almost painfully evident in passages like this one about a teacher (to whom the book is dedicated), “Mrs. Jayne went fast and it was a blessing, but she’s still dead and I still miss her. Unbeknownst to me, she had dutifully attended my college graduation twenty years ago, wearing her best church clothes in hundred-degree weather. She waited three hours to see me receive my diploma, except I didn’t go. I was already financing my departure by moving refrigerators out of dorms. Mrs. Jayne listened for my name being called without answer.”

Other aspects of the generosity he’s capable of might not be so evident in print.

There are other things a critic might (understandably) not know.

(As Saturday’s article so eloquently points out, “A hero is someone who does good when nobody is watching.”)

For example, Offutt never writes about the endless array of students with whom he corresponds – offering advice, encouragement, and support.

He would never brag about the future authors who will probably go on to owe their literary careers to him, the way another generation once owed theirs to the support of a Gurney Norman.

And it’s possible that his critics didn’t attend his speaking engagement at Transylvania this past November (or any of a half dozen others over the years) – where everyone is treated to his unflagging patience, while he stays for hours, until the last book’s signed – but more importantly, until he has heard every last story that each student, faculty member, and fan has shown up to share with him.

When Flannery O’Connor was asked in a classroom lecture if the universities stifled too many young writers, her response was that, in her opinion, the universities didn’t stifle enough of them.

O’Connor was not being condescending; she was talking about the inevitable process of weeding out -Darwin’s culling of the herd – that is true in any field of creative endeavor, whether it’s art (like Offutt, she also has roots as a visual artist), literature, music, or some other path.

She had little sympathy for the students or adults who “fancied themselves writers” and then complained when she gave them her frank assessment of their work.

O’Connor, writing in the shadow of Faulkner, was also never at a loss for words when it came to her native south (having left it for Iowa, and then the northeast until failing health brought her home) – unsparing and relentless in exposing its foibles (racism, a poor education system, and unforgiving poverty, to name a few), her observations on her home country sometimes wore the air of an exasperated parent – a person who wants the best for his child, and can see unrealized potential where perhaps others might see only the flaws.

Offutt (who begins his collection, Out of the Woods, with the above quotation from O’Connor’s Wise Blood) is not arrogant, but he’s also not especially romantic, or sentimental.

He is candid. Sometimes brutally. (And most always, about himself, before others.)

At times, it seems his brain has turned off that polite, sociopolitical filter that most of us employ for daily professional and personal interaction.

And God bless him for it.

I wanted to write a book that acknowledged the harshness of life in the hills, but refused to continue the popular lies I had lived in eastern Kentucky most of my life and had never met anyone resembling the characters in Lil Abner, the Dukes of Hazzard, The Beverly Hillbillies, or Deliverance. Nor had I ever met the flipside of these stereotypes – the simple but noble mountaineer, or the long suffering provincial who lived a pure life, or the person living in bliss due to ignorance.

-Chris Offutt, Ace Weekly, November 16, 2000

Offutt’s disdain for Deliverance’s stereotypes is well-known (though he appreciates the music) – a fact that resurfaces in No Heroes, when he has an exchange with “Nine Mile” (with whom he attended high school, so known for his ability to run fast – now a logger and tobacco farmer, missing two fingers) about the movie at the local video store.

Nine Mile commiserates with him, but his problem with the movie is accuracy: “At the end when the arrow sticks out of his chest. As close as he was, it’d go right through him.”

Offutt has no quarrel with the argument, only responds that he hadn’t thought of that.

Asked by Offutt what he thinks about the “country people” in the movie, Nine Mile offers the assessment “a pretty rough bunch, if you ask me. I’d not fool with them. They’re from so far back in the hills they went toward town to hunt.”

In another exchange with a fellow native, Harley (who’s relocated, across the county line), observes of their shared history, “Ain’t it awful how they done Morehead? I’d not live here for ten dollars a day. And son, Haldeman’s gone, just gone. It’s like our backyard got took away.”

Offutt’s subsequent observation is to muse on their commonality more than their different paths, “Our agreement on loss made perfect sense to Harley. It meant nothing that I had traveled half a million miles to his ten, that we both quit drinking, that we hadn’t seen each other in many years. All that mattered was having grown up together. No one can ever know a Haldeman boy like another Haldeman boy.”

What follows is a few pages of the two of them reminiscing in Harley’s Pinto, and their conversation as Harley shows off his new driver’s license with a spin around the block at funereal pace.

Toward the end of their reunion, Harley says, or asks, “Haldeman was nice wasn’t it,” and upon Offutt’s acquiescence, he concludes, “I got to where I had to leave there,” adding, “Sometimes I miss it.”

And Offutt agrees.

And the conflicted emotions that the two share are as palpable as they are poignant.

Offutt sums it up in the book’s final lines, “I want to stay home. I am ready to leave.”

The Sound and the Fury: Appalachia’s Guard Dogs

What to do? Stay green

Never mind the machine,

Whose fuel is human souls

Live large, man, and dream small.

-R.S. Thomas

The guard dogs of Appalachian culture are – no doubt – a fierce bunch. Some would argue, defensive, and others would add, rightly so.

Charles Kuralt’s do-goodin’ delight at the images of children eating dirt for the holidays didn’t do any of us any favors (for example).

Then again, our image didn’t exactly improve when Letcher County’s Hobart Ison murdered Canadian filmmaker Hugh O’Connor in 1967.

(That story has been told, and told well: thinly veiled in the late Belinda Mason’s unfinished play, The War on Poverty, as well as in Elizabeth Barret’s Appalshop documentary, Stranger with a Camera).

That bullet’s trajectory is palpable, in many ways, to this day.

One of the most grievous insults to our culture came with Robert Schenkkan’s 1992 Pulitzer-Prize winning play, The Kentucky Cycle – six hours of “drama” made no less execrable for such an inexplicable plaudit.

In defending his work, Schenkkan yammered (to everyone who would listen) something about Alexis de Tocqueville and allegory (perhaps presuming we Kentuckians wouldn’t recognize either if they hit us over the head), but the fact remains that he co-opted and bastardized a culture he knew nothing of (but was “exposed to” on a daytrip), and then presumed to pity it, and most offensively, to characterize himself as our “advocate.” (No thanks.)

And the most cardinal sin of all: he did it really, really badly.

Hazard native Shelby Adams’ 1998 book of photography, Appalachian Legacy, arrived to comparable regional scorn and derision.

As a native, he took a much harder, more vicious, and personal hit (as Offutt has with his new book).

Still, at a Perry County picnic celebrating the book’s release, the subjects were in attendance in full force – clearly proud that someone they considered to be one of their own had taken the time to visually preserve their history.

They, and Adams himself, took clear umbrage with the media’s allegations at the time that the poor souls simply didn’t have enough sense to even know they were being exploited.

He said at the time his mission was to “communicate the vulnerability of the human condition to prod the other side a little bit – to force them to confront their own prejudices.”

In 2000, Rory Kennedy came to town with her 1999 documentary as part of HBO’s America Undercover Series, American Hollow.

And Perry County, to put it colloquially, took a collective fit over her portrayal of the Bowlings.

As one native responded at the time, “I live in a $200,000 house in Perry County – how come nobody wants to make a movie about me.”

Most present in the criticism of Kennedy’s work was a fundamental sense of caste that many locals felt she just wasn’t getting: i.e., poverty could be considered an unfortunate circumstance and deserving of empathy – welfare recipients, on the other hand, were not.

The distinction made was that there’s poor, and then there’s just trashy.

Great issue was taken with the fact that she located her subject matter via UK’s Center for Rural Health, who arranged introductions via a social worker. (Kennedy said the film started out as an investigation of welfare reform, and then evolved into more of a biography of one family.)

As Roger Coldiron (a Kentucky native who’d relocated to Maryland) responded at the time, “My father taught my brother and me the value of work and of a disciplined life. I have commanded a Navy destroyer for the past year and a half and my 18-year old daughter is a freshman at Mt. Holyoke. The Bowlings are not sympathetic characters. They are lazy and, as they say in the mountains, ‘sorry.'”

Kennedy met the critics head on, thoughtfully, and with no apologies.

She offered this, “[American Hollow] does not purport to represent all of Kentucky, or all of Appalachia, or all of the South. It’s a very self-contained portrait of one family, living in one of the most impoverished” sections of the state.

Of reaction to the film, author Gurney Norman was willing to go on the record in the most sparing of terms, allowing, “it’s possible we have almost succeeded too well in raising the consciousness about stereotypes” in Appalachia.

On its artistic merits, the film fell pretty far short of the standards set by HBO in other installments of that particular series. And the Bowlings were most assuredly painful to watch. The young son migrates north (to Cincinnat-uh) but – as predicted by kith and kin – fails to make it in the Big City and returns home, chastened. The family seems absurdly pleased.

It has its moments of real pathos.

And it re-opened a dialogue that we clearly weren’t done with.

For her part, Kennedy stressed, “My strategy with poverty is NOT to say that it doesn’t exist. You have to look at these issues.”

Although she found much to celebrate in her documentary, she was equally forthcoming about the problems, “Working is really an important part of life and there are not jobs there. It’s very isolated and there’s lots to be said for having access to diversity and multiculturalism. The roads aren’t paved and it can take police an hour or two to get back there. The education system is lacking. There’s something to be said for being exposed to other types of folks, and not just through a television set.

It’s a sentiment Shelby Adams echoes when he asks, “As we become a TV satellite generation, what are we sacrificing to get to what we consider a livable community.”

No artist – Kentuckian or otherwise-wins any points for denial.

There’s no crime, literary or otherwise, in acknowledging the pink elephant in the room, as Offutt does when he sees his culture paved over and ground under.

“For we are left, but a few of many.”

-Jeremiah 42:2

The time and space Offutt devotes to Wal-Mart’s veritable death-grip on small towns can scarcely come as news to anyone when, in 1998, David Glass, the company’s COO, described his company’s objective as, “First we dominate North America, then South America, then Europe and Asia.” Even documentary filmmaker, Micha Peled, who produced last May’s documentary, Store Wars: When Wal-Mart Comes to Town, could scarcely have conceived how prescient the statement would turn out to be. (For the record, Peled is no Appalachian expatriate traitor. He’s an Israeli who grew up in the farm town of Ganey-Yehuda, which roughly translates as Judas’s Garden.)

Kentucky’s cities (and a lot of others) are filled with expatriates from the hills. Many assimilate. Many adopt (or at least present) an idealized view of “home.” Some drop their accents entirely. Some (for example, author Linda Scott DeRosier, a Ph.D. academic in Montana) still sound exactly as one imagines she did living back on Two-Mile Creek (chronicled in Creeker). She’s successful enough now (as academic and author) that everybody finds it charming – when she was starting out in her academic career, however, she freely admits it got her branded a hick, and that derogatory assumptions were made about her intellect the moment she opened her mouth.

Sure, given a choice, we’d probably all like to pick and choose our stereotypes.

Rolling horse farms and white fences gooooooooood.

Bourbon gooooooood.

Basketball? Go Cats. (Well yeah, sure, we named an Arena after a [by most accounts] racist, but well, wasn’t that another time? And he did win a lot of ballgames.)

Ashley Judd? Went to UK y’know.

George Clooney? Born in a Lexington hospital. Got his acting start here as an extra. (Probably where he picked up that accent for O Brother – an admittedly fine farce, which nobody seemed to have any quarrel with. Maybe because it was made by midwesterners.)

The Down from the Mountain tour? Why yes, of course, we knew it all along. (Though the recent tour got bigger, better media in other towns than it did here, and Garth Brooks and similar hat acts sell far better at Rupp Arena.)

In describing his own mission and vision, Peled quoted Arthur Miller, “Every piece of art should bring news.”

And the news isn’t always good.

That’s no reason to kill the messenger.

The April 13, 2002 article in the Herald-Leader observes, “Judging from the mood of many people in Morehead, Offutt may not be hailed as a conquering hero next time he comes home.”

He wouldn’t be the first.

But it would be a shame.

On the surface, I was giving Rita private tours of my home, but now I realize that I was really trying to learn who I had been 20 years ago, attempting to make peace with my pastThere were changes in my hometown of Haldeman – blacktop instead of dirt roads being the most obvious. My grade school was closed. The post office was closed. The only store was closedBut the land remained – those wondrous hills full of dense foliage. The creeks rushed off the slope to trickle through a hollow.

-Chris Offutt, “The Hot Rod: Wild and loose and at long last, cool,” Ace, July 2000

In July of 2000, Offutt contributed an essay to Ace titled “The Hot Rod.” (A variation on it appears in the new book.)

Both versions are about his love affair with muscle cars, his love affair with his wife Rita, and Rita’s love for the “throbbing engine” and its “speed and power.”

In his 1968 Malibu, he’d suddenly achieved what everybody had wanted back in 1978 Rowan County: the essence of cool.

In both versions, he takes her to Buffalo Hollow, with the same kind of romantic inclinations he’d nursed through high school. Both versions end with picking up the kids at school and taking them for dilly bars at the Dairy Queen.

In the book, they share a kiss at a traffic light.

In the essay, he cuts the engine on the rutted road and they make love.

He tells her about the significance of the location, and the Malibu, and she “suggested I write about it for the new book.”

He responds in protest, “I told her I couldn’t possibly write about sex in a Malibu on a dirt road in the middle of the day in the hills. People might get the wrong idea. They might think I was wild and loose.”

And in the essay, she answers with a truth that isn’t going to be denied because of a bad review here or there, “You can write about anything you want, Chris. You’re a writer.”

###

Bio

Offutt graduated from Morehead State University, with a degree in theater and minor in art-later attending Iowa’s famous writing program, where he was awarded the Michener Grant-which provided him the resources to write his first two critically-lauded books.

His debut collection of stories, Kentucky Straight (1992) won him awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Whiting Foundation. He also made the list of Granta’s 20 Best Young Fiction Writers.

He followed up with The Same River Twice.

In 1997, Simon and Schuster published his first novel, The Good Brother (voted best book by a Kentucky author by Ace readers, who called it everything from The Good Son to the Good First-Cousin Twice Removed).

Out of the Woods was published in 1999. One of the selections, “Melungeons,” was included in Best American Short Stories (1994)

He’s lived in New York, Massachusetts, Iowa, Montana, and New Mexico, to name a few.

Selected Reading

Another Turn of the Crank, by Wendell Berry.

Confronting Appalachian Stereotypes: Back Talk from an American Region, edited by Dwight Billings, Gurney Norman, and Katherine Ledford

Creeker, by Linda Scott DeRosier

The Road to Poverty: The Making of Wealth and Hardship in Appalachia, by Dwight B. Billings and Kathleen M. Blee

Night Comes to the Cumberlands, by Harry Caudill